First string confusion decisions handed down, Verisign loses against .tvs

The International Centre for Dispute Resolution has started delivering its decisions in new gTLD String Confusion Objections, and we can report that Verisign has lost at least one case.

ICDR expert Stephen Strick delivered a brief, five-page ruling in the case of Verisign vs. T V Sundram Iyengar & Sons yesterday, ruling that .tvs is not confusingly similar to .tv.

TVS is a $6-billion-a-year, 100-year-old Indian conglomerate, while .tv is the ccTLD for Tuvalu, which Verisign manages because of its similarity of meaning to “television”.

It’s impossible to glean from the decision (pdf) what Verisign’s argument comprised. The summary is just two sentences long.

But TVS, in response, appears to have relied to an extent on the “DuPont factors” a 13-point test for trademark confusion that came out of a 1973 case in the US.

That’s the same precedent that has been found relevant in many Legal Rights Objections in cases handled by WIPO.

The “discussion and reasons for determination” section of the .tvs decision, in which Strick found that confusion was possible but not “probable”, amounts to just four sentences.

Here’s almost all of it. Emphasis in original:

in order for the Objector to prevail, Objector must prove that the co-existence of the two TLDs in question would probably result in user confusion. Given the analysis of the thirteen factors cited by Applicant derived from the DuPont case cited above, I find that Objector has failed to meet its burden of proof regarding the probability of such confusion. I note that while the co-existence of the two TLDs that are the subject of this proceeding may result in confusion by users, Objector has failed to meet its burden of proof to establish the likelihood or probability that users will be confused.

In considering parties’ arguments, I was persuaded, in part, by Applicant’s arguments relating to the commercial impression of the TVS TLD, including the proof offered by Applicant as to the longevity of the TVS brand, the limited nature of the gTLD’s intended use, the dissimilarity of the goods or services associated respectively with the two strings, ie TVS’s association with automobile products, the fact that TVS’s brand is associated with capital letters (whereas Objector’s .tv is in lower case), the fact that TVS is well known and associated with its companys’ [sic] brands, the lengthy market interface and the long historical co-existence of TVs and tv without evidence of confusion in the marketplace.

The geeks among you will no doubt be screaming at your screen right now: “WTF? He thought CASE was relevant?”

Yes, apparently the fact that the TVS trademark is in upper case makes a difference, despite the fact that the DNS is completely case-insensitive. Bit of a head-scratcher.

I understand several more decisions have also been sent to applicants and objectors, but they’re not yet pubicly available.

The ICDR’s web site for new gTLD decisions has been down for several days, returning 404 errors.

New US trademark rules likely to exclude many dot-brand gTLDs

The US Patent and Trademark Office plans to allow domain name registries to get trademarks on their gTLDs.

Changes proposed this week seem to be limited to dot-brand gTLDs and would not appear to allow registries for generic strings — not even “closed” generics — to obtain trademarks.

But the rules are crafted in such a way that single-registrant dot-brands might be excluded.

Under existing USPTO policy, applications for trademarks that consist solely of a gTLD cannot be approved, because they don’t identify the source of goods and services.

If “.com” were a trademark, one might have to assume that the source of Amazon.com’s services was Verisign, which is plainly not the case.

But the new gTLD program has invited in hundreds of gTLDs that exactly match existing trademarks. The USPTO said:

Some of the new gTLDs under consideration may have significance as source identifiers… Accordingly, the USPTO is amending its gTLD policy to allow, in some circumstances, for the registration of a mark consisting of a gTLD for domain-name registration or registry services

In order to have a gTLD trademark approved, the applicant would have to pass several tests, substantially reducing the number of marks that would get the USPTO’s blessing.

First, only companies that have signed a Registry Agreement with ICANN would be able to get a gTLD trademark. That should continue to prohibit “front-running”, in which a gTLD applicant tries to secure an advantage during the application process by getting a trademark first.

Second, the registry would have to own a prior trademark for the gTLD string in question. It would have to exactly match the gTLD, though the dot would not be considered.

It would have to be a word mark, without attached disclaimers, for the same types of goods and services that web sites within the gTLD are supposed to provide.

What this seems to mean is that registries would not be able to get trademarks on closed generics.

You can’t get a US trademark on the word “cheese” if you sell cheese, for example, but you can if you sell a brand of T-shirts called Cheese.

So you could only get a trademark on “.cheese” as a gTLD if the class was something along the lines of “domain name registration services for web sites devoted to selling T-shirts”.

Third, registries would have to present a bunch of other evidence demonstrating that their brand is already so well-known that consumers will automatically assume they also own the gTLD:

Because consumers are so highly conditioned and may be predisposed to view gTLDs as non-source indicating, the applicant must show that consumers already will be so familiar with the wording as a mark, that they will transfer the source recognition even to the domain name registration or registry services.

Fourth, and here’s the kicker, the registry would have to show it provides a “legitimate service for the benefit of others”. The USPTO explained:

To be considered a service within the parameters of the Trademark Act, an activity must, inter alia, be primarily for the benefit of someone other than the applicant.

…

While operating a gTLD registry that is only available for the applicant’s employees or for the applicant’s marketing initiatives alone generally would not qualify as a service, registration for use by the applicant’s affiliated distributors typically would.

In other words, a .ford as a single-registrant gTLD would not qualify for a trademark, but a .ford that allowed its dealerships around the world to register domains would.

That appears to exclude many dot-brand applicants. In the current batch, most dot-brands expect to be the sole registrant as well as the registry, at least at first.

Some applications talk in vague terms about also opening up their namespace to affiliates, but in most applications I’ve read that’s a wait-and-see proposition.

The new USPTO rules, which are open for comment to people who have registered with its web site, would appear to apply to a very small number of applicants at this stage.

The UK is going nuts about porn and Go Daddy and Nominet are helping

In recent months the unhinged right of the British press has been steadily cajoling the UK government into “doing something about internet porn”, and the government has been responding.

I’ve been itching to write about the sheer level of badly informed claptrap being aired in the media and halls of power, but until recently the story wasn’t really in my beat.

Then, this week, the domain name industry got targeted. To its shame, it responded too.

Go Daddy has started banning certain domains from its registration path and Nominet is launching a policy consultation to determine whether it should ban some strings outright from its .uk registry.

It’s my beat now. I can rant.

For avoidance of doubt, you’re reading an op-ed, written with a whisky glass in one hand and the other being used to periodically wipe flecks of foam from the corner of my mouth.

It also uses terminology DI’s more sensitive readers may not wish to read. Best click away now if that’s you.

The current political flap surrounding internet regulation seems emerged from the confluence of a few high-profile sexually motivated murders and a sudden awareness by the mainstream media — now beyond the point of dipping their toes in the murky social media waters of Twitter — of trolls.

(“Troll” is the term, rightly or wrongly, the mainstream media has co-opted for its headlines. Basically, they’re referring to the kind of obnoxious assholes who relentlessly bully others, sometimes vulnerable individuals and sometimes to the point of suicide, online.)

In May, a guy called Mark Bridger was convicted of abducting and murdering a five-year-old girl called April Jones. It was broadly believed — including by the judge — that the abduction was sexually motivated.

It was widely reported that Bridger had spent the hours leading up to the murder looking at child abuse imagery online.

It was also reported — though far less frequently — that during the same period he had watched a loop of a rape scene from the 2009 cinematic-release horror movie Last House On The Left

He’d recorded the scene on a VHS tape when it was shown on free-to-air British TV last year.

Of the two technologies he used to get his rocks off before committing his appalling crime, which do you think the media zeroed in on: the amusingly obsolete VHS or the golly-it’s-all-so-new-and-confusing internet?

Around about the same time, another consumer of child abuse material named Stuart Hazell was convicted of the murder of 12-year-old Tia Sharp. Again it was believed that the motive was sexual.

While the government had been talking about a porn crackdown since 2011, it wasn’t until last month that the prime minister, David Cameron, sensed the time was right to announce a two-pronged attack.

First, Cameron said he wants to make it harder for people to access child abuse imagery online. A noble objective.

His speech is worth reading in full, as it contains some pretty decent ideas about helping law enforcement catch abusers and producers of abuse material that weren’t well-reported.

But it also contained a call for search engines such as Bing and Google to maintain a black-list of CAM-related search terms. People search for these terms will never get results, but they might get a police warning.

This has been roundly criticized as unworkable and amounting to censorship. If the government’s other initiatives are any guide, it’s likely to produce false positives more often than not.

Second, Cameron said he wants to make internet porn opt-in in the UK. When you sign up for a broadband account, you’ll have to check a box confirming that you want to have access to legal pornography.

This is about “protecting the children” in the other sense — helping to make sure young minds are not corrupted by exposure to complex sexual ideas they’re almost certainly not ready for.

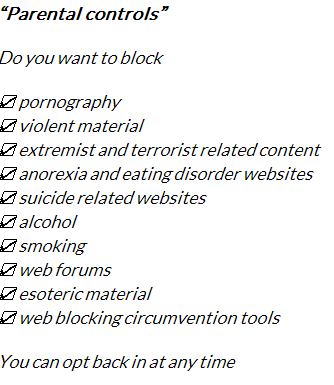

The Open Rights Group has established that the opt-in process will look a little like this:

Notice how there are 10 categories and only one of them is related to pornography? As someone who writes about ICANN on a daily basis, I’m pretty worried about “esoteric materials” being blocked.

As a related part of this move, the government has already arranged with the six largest Wi-Fi hot-spot operators in the country to have porn filters turned on by default.

I haven’t personally tested these networks, but they’re apparently using the kind of lazy keyword filters that are already blocking access to newspaper reports about Cameron’s speech.

Censorship, in the name of “protecting the children” is already happening here in the UK.

Which brings me to Nominet and Go Daddy

Last Sunday, a guy called John Carr wrote a blog post about internet porn in the UK.

I can’t pretend I’ve ever heard of Carr, and he seems to have done a remarkably good job of staying out of Google, but apparently he’s a former board member of the commendable CAM-takedown charity the Internet Watch Foundation and a government adviser on online child safety.

He’d been given a preview of some headline-grabbing research conducted by MetaCert — a web content categorization company best known before now for working with .xxx operator ICM Registry — breaking down internet porn by the countries it is hosted in.

Because the British rank was surprisingly high, the data was widely reported in the British press on Monday. The Daily Mail — a right-wing “quality” tabloid whose bread and butter is bikini shots of D-list teenage celebrities — on Monday quoted Carr as saying:

Nominet should have a policy that websites registered under the national domain name do not contain depraved or disgusting words. People should not be able to register websites that bring disgrace to this country under the national domain name.

Now, assuming you’re a regular DI reader and have more than a passing interest in the domain name industry, you already know how ludicrous a thing to say this is.

Network Solutions, when it had a monopoly on .com domains, had a “seven dirty words” ban for a long time, until growers of shitake mushrooms and Scunthorpe Council pointed out that it was stupid.

You don’t even need to be a domain name aficionado to have been forwarded the hilarious “penisland.net” and “therapistfinder.com” memes — they’re as old as the hills, in internet terms.

Assuming he was not misquoted, a purported long-time expert in internet filtering such as Carr should be profoundly, deeply embarrassed to have made such a pronouncement to a national newspaper.

If he really is a government adviser on matters related to the internet, he’s self-evidently the wrong man for the job.

Nevertheless, other newspapers picked up the quotes and the story and ran with it, and now Ed Vaizey, the UK’s minister for culture, communications and creative industries, is “taking it seriously”.

Vaizey is the minister most directly responsible for pretending to understand the domain name system. As a result, he has quite a bit of pull with Nominet, the .uk registry.

Because Vaizey for some reason believes Carr is to be taken seriously, Nominet, which already has an uncomfortably cozy relationship with the government, has decided to “review our approach to registrations”.

It’s going to launch “an independently-chaired policy review” next month, which will invite contributions from “stakeholders”.

The move is explicitly in response to “concerns” about its open-doors registration policy “raised by an internet safety commentator and subsequently reported in the media.”

Carr’s blog post, in other words.

Nominet — whose staff are not stupid — already knows that what Carr is asking for is pointless and unworkable. It said:

It is important to take into account that the majority of concerns related to illegality online are related to a website’s content – something that is not known at the point of registration of a domain name.

But the company is playing along anyway, allowing a badly informed blogger and a credulous politician to waste its and its community’s time with a policy review that will end in either nothing or censorship.

What makes the claims of Carr and the Sunday Times all the more extraordinary is that the example domain names put forward to prove their points are utterly stupid.

Carr published on his blog a screenshot of Go Daddy’s storefront informing him that the domain rapeher.co.uk is available for registration, and wrote:

www.rapeher.co.uk is a theoretical possibility, as are the other ones shown. However, I checked. Nominet did not dispute that I could have completed the sale and used that domain.

…

Why has it not occurred to Nominet to disallow names of that sort? Nominet needs to institute an urgent review of its naming policies

To be clear, rapeher.co.uk did not exist at the time Carr wrote his blog. He’s complaining about an unregistered domain name.

A look-up reveals that kill-all-jews.co.uk isn’t registered either. Does that mean Nominet has an anti-Semitic registration policy?

As a vegetarian, I’m shocked and appalled to discovered that vegetarians-smell-of-cabbage.co.uk is unregistered too. Something must be done!

Since Carr’s post was published and the Sunday Times and Daily Mail in turn reported its availability, five days ago, nobody has registered rapeher.co.uk, despite the potential traffic the publicity could garner.

Nobody is interested in rapeher.co.uk except John Carr, the Sunday Times and the Daily Mail. Not even a domainer with a skewed moral compass.

And yet Go Daddy has took it upon itself, apparently in response to a call from the Sunday Times, to preemptively ban rapeher.co.uk, telling the newspaper:

We are withdrawing the name while we carry out a review. We have not done this before.

This is what you see if you try to buy rapeher.co.uk today:

Is that all it takes to get a domain name censored from the market-leading registrar? A call from a journalist?

If so, then I demand the immediate “withdrawal” of rapehim.co.uk, which is this morning available for registration.

Does Go Daddy not take male rape seriously? Is Go Daddy institutionally sexist? Is Go Daddy actively encouraging male rape?

These would apparently be legitimate questions, if I was a clueless government adviser or right-leaning tabloid hack under orders to stir the shit in Middle England.

Of the other two domains cited by the Sunday Times — it’s not clear if they were suggested by Carr or MetaCert or neither — one of them isn’t even a .co.uk domain name, it’s the fourth-level subdomain incestrape.neuken.co.uk.

There’s absolutely nothing Nominet, Go Daddy, or anyone else could do, at the point of sale, to stop that domain name being created. They don’t sell fourth-level registrations.

The page itself is a link farm, probably auto-generated, written in Dutch, containing a single 200×150-pixel pornographic image — one picture! — that does not overtly imply either incest or rape.

The links themselves all lead to .com or .nl web sites that, while certainly pornographic, do not appear on cursory review to contain any obviously illegal content.

The other domain cited by the Daily Mail is asian-rape.co.uk. Judging by searches on several Whois services, Google and Archive.org, it’s never been registered. Not ever. Not even after the Mail’s article was published.

It seems that the parasitic Daily Mail really, really doesn’t understand domain names and thought it wouldn’t make a difference if it added a hyphen to the domain that the Sunday Times originally reported, which was asianrape.co.uk.

I can report that asianrape.co.uk is in fact registered, but it’s been parked at Sedo for a long time and contains no pornographic content whatsoever, legal or otherwise.

It’s possible that these are just idiotic examples picked by a clueless reporter, and Carr did allude in his post to the existence of .uk “rape” domains that are registered, so I decided to go looking for them.

First, I undertook a series of “rape”-related Google searches that will probably be enough to get me arrested in a few years’ time, if the people apparently guiding policy right now get their way.

I couldn’t find any porn sites using .uk domain names containing the string “rape” in the first 200 results, no matter how tightly I refined my query.

So I domain-dipped for a while, testing out a couple dozen “rape”-suggestive .co.uk domains conjured up by my own diseased mind. All I found were unregistered names and parked pages.

I Googled up some rape-themed porn sites that use .com addresses — these appear to exist in abundance, though few appear to contain the offending string in the domain itself — and couldn’t find any that have bothered to even defensively register their matching .co.uk.

So I turned to Alexa’s list of the top one million most-popular domains. Parsing that (.csv), I counted 277 containing the string “rape”, only 32 of which (11%) could be loosely said to be using it in the sense of a sexual assault.

Whether those 32 sites contain legal or illegal pornographic content, I couldn’t say. I didn’t check. None of them were .uk addresses anyway.

Most of the non-rapey ones were about grapes.

I’m not going to pretend that my research was scientific, neither am I saying that there are no rape-themed .co.uk porn sites out there, I’m just saying that I tried for a few hours to find one and I couldn’t.

What I did find were dozens of legitimate uses of the string.

So if Nominet bans the word “rape” from domain name registrations under .uk — which is what Carr seems to want to happen — what happens to rapecrisis.org.uk?

Does the Post Office have to give up grapevine.co.uk, which it uses to help prevent crime? Does the eBay tools provider Terapeak have to drop its UK presence? Are “skyscrapers” too phallic now? Is the Donald Draper Fan Club doomed?

And what about the fine fellows at yorkshirerapeseedoil.co.uk or chilterncoldpressedrapeseedoil.co.uk?

If these examples don’t convince you that a policy of preemptive censorship would be damaging and futile, allow me to put the question in terms the Daily Mail might understand: why does Ed Vaizey hate farmers?

We have a winner! Del Monte wins .delmonte LRO

No sooner did I predict the new gTLD Legal Rights Objection would not produce any prevailing complainants in this application round, then I’ve been proved wrong.

A three-person WIPO panel yesterday delivered a majority-verdict win for Del Monte, which had filed an LRO against its licensee, .delmonte new gTLD applicant Fresh Del Monte.

It’s a complex case, but the panelists’ thinking appears to be consistent with previously decided LROs.

Del Monte is the original owner of the Del Monte brand, with rights going back to the nineteenth century and registered trademarks all over the world.

Fresh Del Monte has used the Del Monte brand under license from the other company since 1989.

Fresh Del Monte also acquired a South African trademark for “Del Monte” in October 2011, but the panel viewed this with suspicion, wondering aloud whether it had been obtained just to bolster its new gTLD application.

The panel also wondered whether acquiring the mark may have been a breach of the two firms’ longstanding licensing agreement.

The circumstances behind the South African trademark were enough to convince two of the three panelists that there was “something untoward” about Fresh Del Monte’s behavior.

That was a crucial factor in the decision (pdf), with the panel citing earlier LRO precedent to the effect that there must be some kind of bad faith present by the applicant in order for an LRO to succeed.

But the most important factor, according to the decision, was the “likelihood of confusion” element of the LRO. The panelists wrote:

From the crucial perspective of the average consumer, and notwithstanding the somewhat complicated licensing arrangements, the coexistence of the parties’ products in certain territories, and the similarity of the parties’ coexisting food products, the evidence shows that the Trade Mark has continued to function as an indicator of the commercial origin of the Objector and its goods (whether the Objector’s direct goods, or licensed goods).

They’re not wrong. Both companies sell canned fruit and vegetables and use the same logo. It’s virtually impossible for the average guy in the street to tell the difference between the two.

Having been exposed to the Del Monte brand for as long as I can remember, having read the LRO decision, and having visited both companies’ web sites, I still couldn’t tell you which company’s canned pineapple I’ve been ignoring on supermarket shelves all these years.

But the decision was not unanimous. Dissenting panelist Robert Badgley agreed with most of the panel’s findings but thought they hadn’t given enough weight to Fresh Del Monte’s South African trademark.

The panel, he suggested, hadn’t looked closely enough at the circumstances of the trademark rights being acquired because it hadn’t allowed additional submissions on that point.

Basically, the decision seems to have been made on partial evidence. Badgley wrote:

I am prepared to conclude that it is more likely than not that Respondent owns the DEL MONTE mark in South Africa and its use of that mark has been bona fide. This conclusion is critical to my ultimate view that Objector has failed to carry its burden of proof and therefore the Objection should be overruled.

He also noted that the two companies, with their matching brands, had been coexisting for 24 years under their licensing arrangement.

That’s all folks, no more LRO news

The results of Legal Rights Objections against new gTLD applications are no longer news.

That’s the decision handed down by the editor here at DI’s Global World International Headquarters today.

“Hey, Keith,” she barked from her ermine-carpeted corner office. “This LRO stuff is getting a bit old, don’t you think?”

“My name’s Kevin,” I said.

“Whatever,” she said. “LRO is now dog-bites-man. I decree it thus. No more of it, understand? Write more about Go Daddy girls.”

She has a point (she’s a great editor and I love her dearly).

The Legal Rights Objection has, I think, said pretty much everything it’s going to say in this new gTLD application round. I’m feeling pretty confident we can predict that all outstanding LROs will fail.

This prediction is based largely on the fact that the 69 LROs filed in this round all pretty much fall into three categories.

- Front-running. These are the cases where the objector is an applicant that secured a trademark on its chosen gTLD string, usually with the dot, just in order to game the LRO process. These have all been rejected so far. I thought Constantine Roussos’ .music objection was the only one with a sliver of a chance; now that it’s been rejected I think the chances of any outstanding objections of this type prevailing are zero.

- Brand v Brand. The objector may or may not be an applicant too, but both it and the respondent both own legit trademarks on the string in question. WIPO’s LRO panelists have made it clear, most recently yesterday in Merck v Merck (pdf) and Merck v Merck (pdf), that having a famous brand does not give you the right to block somebody else from owning a matching famous brand as a gTLD.

- Generic trademarks. Cases where an owner of a legit brand that matches a dictionary word files an objection against an applicant for the same string that proposes to use it in its generic sense. See Express v Donuts, for example. Panelists have found that unless there’s some nefarious intent by the applicant, the mandatory second-level rights protection mechanisms new gTLD registries must abide by are sufficient to protect trademark rights. As I don’t believe any applicants have a nefarious intent, I don’t believe any of these LROs will succeed.

In short, the LRO may be one of many deterrents to top-level cybersquatting, but has proven itself an essentially useless cash sink if you want to prevent the use of a trademark at the top level.

The impact of this, I believe, will be to give new gTLD consultants another excellent reason to push defensive gTLD applications on big brands in future new gTLD rounds.

Whether it will inspire unsavory types to apply for generic terms in future, in order to extort money from matching brands, will depend to a large extent on whether applicants in this round wind up making lucrative deals with the brands they’re competing against.

In any event, it seems certain that the LRO-to-application ratio will be far lower in future rounds.

DI will of course continue to peruse each new LRO as it is published and will report on any genuinely interesting developments, but we will not cover each decision as a matter of course.

Decisions are published by WIPO daily here and email notifications are sent along with WIPO’s daily UDRP newsletter.

Information about Go Daddy girls can, from now on, be found here.

DotMusic loses LRO, and four other cases rejected

Constantine Roussos has lost his first Legal Rights Objection over the flagship .music gTLD.

The case, DotMusic v Charleston Road Registry (pdf) was actually thrown out on a technicality — DotMusic didn’t present any evidence to show that it was the owner of the trademarks in question.

But the WIPO panelist handling the case made it pretty clear that DotMusic wouldn’t have won on the merits anyway.

If any applicant can be said to have built a brand around a proposed generic-term gTLD, it’s Roussos. DotMusic has been promoting .music on social media an in the music industry for years.

The company also owns the string “music” in a number of second-tier TLDs such as .co, .biz and .fm.

It’s not a bogus, last-minute attempt to game the system, like the .home cases — filed using Roussos-acquired trademarks — that have been thrown out repeatedly over the last couple of weeks.

The panelist addressed this directly:

On the one hand, the Panel recognizes that there has been a real investment by the Objector and associated parties in the trademark registrations, domain name registrations, sponsorship and branding to create consumer recognition and goodwill entitled to protection. On the other hand, there is a circularity in the Objector’s position in that the rights upon which the Objector relies to defeat the application are to a certain extent conditional on the defeat of the Applicant and the Objector’s success in obtaining the <.music> gTLD string.

In other words, Catch-22.

The panelist decided that .music is generic, that Google’s proposed use of it is generic, and that obtaining a trademark on a gTLD should not be a legit way to exclude rival applicants for that gTLD.

One objective of the Objector has been to obtain precisely the type of competitive advantage (in this case in the application process for the <.music> gTLD string) that the doctrine of generic names is designed to prevent. However, as the Applicant proposes to use the <.music> gTLD string in a generic sense it is immune from this challenge.

On that basis, the LRO would have failed, had DotMusic managed to demonstrate standing to object in the first place.

Unfortunately, DotMusic didn’t present any evidence that it actually owned the trademarks in question, which were applied for by Roussos and assigned to his company CGR E-Commerce.

The objection failed on that basis.

Defender Security, which obtained trademarks on “.home” from Roussos, ran into the same problems proving ownership of the trademarks in its LROs on the .home gTLD.

Four other LROs were decided this week:

.mail (United States Postal Service v. GMO Registry)

The case (pdf) turned on whether USPS owns a trademark that exactly matches the applied-for string (it doesn’t) and whether the word “mail” should be considered generic (it is) rather than a source identifier (it isn’t).

It’s pretty much the same logic applied in the two previous .mail LROs.

.food (Scripps Networks Interactive v. Dot Food, LLC)

This is the first of two competitive LROs filed by Scripps — which runs TV stations including the Food Network — against its .food applicant rivals to be decided.

Scripps has a bunch of trademarks containing the word “food”, including a November 2011 registration in the US for “Food” alone, covering entertainment services.

The WIPO panelist found (pdf) that the trademark was legit, but decided that it was not enough to prevent Dot Food using the matching string as a gTLD.

The fact that rights protection mechanisms exist in the new gTLD program was key:

to the extent that registration and use of a particular second-level domain within the <.food> gTLD actually creates a likelihood of confusion, then Objector will have remedies available to it, including the established Uniform Domain Name Dispute Resolution Policy, the forthcoming Uniform Rapid Suspension System and relevant laws. The fact that such disputes at the second level may arise is inherent in ICANN’s new gTLD program and is not in the circumstances of this case sufficient to uphold the present legal rights objection.

Objector’s rights in the FOOD mark do not confer upon it the exclusive right to use of the word “food” in all circumstances, particularly where, as here, Applicant intends to use the <.food> gTLD in connection with the food industry. Such intended use of the word would appear to be only for its dictionary meaning and not because of Objector’s trademark rights.

.vip (i-Registry v. Charleston Road Registry)

It’s the second objection by .vip applicant to get thrown out. In this case the respondent was Google.

Like the first time, the WIPO panelist found that the i-Registry trademark had been obtained for the purposes of the new gTLD program and that Google’s use of it in its generic sense would not infringe its rights.

.cam (AC Webconnecting Holding v. Dot Agency)

The second and final LRO decision (pdf) in the .cam contention set.

AC Webconnecting, an operator of webcam-based porn sites, lost again on the grounds that it applied for its trademark just a month before ICANN opened up the new gTLD application window in January last year.

The company didn’t have time to, and produced no evidence to suggest that, it had used the trademark and built up goodwill around “.cam” in the normal course of business.

In other words, front-running doesn’t pay.

URS is live today as .pw voluntarily adopts it

Directi has become the first TLD registry to start complying with the Uniform Rapid Suspension process for cybersquatting complaints.

From today, all .pw domain name registrations will be subject to the policy, which enables trademark owners to have domains suspended more quickly and cheaply than with UDRP.

URS was designed, and is obligatory, for all new gTLDs, but Directi decided to adopt the policy along with UDRP voluntarily, to help mitigate abuse in the ccTLD namespace.

URS requirements for gTLD registries have not yet been finalized, but this is moot as they don’t apply to .pw anyway.

To date, only two UDRP complaints have been filed over .pw domains.

The National Arbitration Forum will be handling URS complaints. Instructions for filing can be found here.

Six more LROs kicked out, most for “front-running”

Six more new gTLD Legal Rights Objections, six more rejected objections.

The World Intellectual Property Organization is chewing through its caseload of LROs at a regular pace now, made all the more easier by the fact that a body of precedent is being accumulated.

Objections rejected in decisions published last week cover the gTLDs .home, .song, .yellowpages, .gmbh and .cam.

All but one were thrown out, with slightly different panelist reasoning, because they had engaged in some measure of “front-running” — applying for a trademark just in order to protect a gTLD application.

Here’s a quick summary of each decision, starting with what looks to be the most interesting:

.yellowpages (hibu (UK) v. Telstra)

Last week somebody asked me on Twitter which LROs I thought might actually succeed. I replied:

@ManagingIP Just based on the list of strings and objectors, only .delmonte, .merck and .yellowpages jump out at me.

— Kevin Murphy (@DomainIncite) July 23, 2013

Well, my initial hunch on .yellowpages was wrong, and I think I’m very likely to have been wrong about the other two also.

This case is interesting because it specifically addresses the issue of two matching trademarks happily living side-by-side in the trademark world but clashing horribly in the unique gTLD space.

The objector in this case, hibu, publishes the Yellow Pages phone book in the UK and has a big portfolio of trademarks and case law protecting its brand. If anyone has rights, it’s these guys.

But the “Yellow Pages” brand is used in several countries by several companies. In the US, there’s some case law suggesting that the term is now generic, but that’s not the case in the UK or Australia.

On the receiving end of the objection was the Australian telecoms firm Telstra, which is the publisher of the Aussie version of the Yellow Pages and, luckily for it, the only applicant for .yellowpages.

The British company argued that “no party should be entitled to register the Applied-for gTLD”, due to the potential for confusion between the same brand being owned by different companies in different countries.

The panel concluded that brands will clash in the new gTLD space, and that that’s okay:

It is inherent in the nature of the gTLD regime that those applicants who are granted gTLDs will have first-level power extending throughout the Internet and across jurisdictions. The prospect of coincidence of brand names and a likelihood of confusion exists.

…

The critical issue in this LRO proceeding is whether the Objector’s territorial rights in the term “YELLOW PAGES” (and the prospect of other non-objecting third parties’ territorial right) means that the applicant (or anyone else for that matter) should not be entitled to the Applied-for gTLD.

The panelist uses the eight-criteria test in the Applicant Guidebook to make his decision, but he chose to highlight two words:

the Panel finds that the Objector has failed to establish, as it alleges, that the potential use of the Applied-for gTLD by the applicant… unjustifiably impairs the distinctive character or the reputation of the objector’s mark… or creates an impermissible likelihood of confusion between the applied for gTLD and the Objector’s mark.

Because Telstra has rights to “Yellow Pages” too, and because it’s promising to respect trademark rights at the second level, the panelist concluded that its application should be allowed to proceed.

It’s the third instance of a clash between rights holders in the LRO process and the third time that the WIPO panelist has adopted a laissez faire approach to new gTLDs.

And as I’ve said twice before, if this type of decision becomes the norm — and I think it will — we’re likely to see many more defensive applications for brand names in future new gTLD rounds.

The LRO is not shaping up to be an alternative to applying for a gTLD as a means to defend a legitimate brand. Applying for a gTLD matching your trademark and then fighting through the application process may turn out to be the only way to make sure nobody else gets that gTLD.

.cam (AC Webconnecting Holding v. United TLD Holdco)

Both sides of this case are applicants for .cam. United TLD is a Demand Media subsidiary while AC Webconnecting is a Netherlands-based operator of several webcam-based porn sites.

Like so many other applicants, AC Webconnecting applied for its European trademark registration for “.cam” and a matching logo in December 2011, just before the ICANN application window opened.

The panelist decided that its trademark was acquired in a bona fide fashion, he also decided that the company had not had enough time to build up a “distinctive character” or “reputation” of its marks.

That meant the Demand Media application could not be said to take “unfair advantage” of the marks. The panelist wrote:

Given the relatively short existence of these trademarks, it is unlikely that either [trademark] has developed a reputation.

…

In the Panel’s opinion, replication of a trademark does not, of itself, amount to taking unfair advantage of the trademark – something more is required.

…

the Panel considers that this something more in the present context needs to be along the lines of an act that has a commercial effect on a trademark which is undertaken in bad faith – such as free riding on the goodwill of the trademark, for commercial benefit, in a manner that is contrary to honest commercial practices.

What we’re seeing here is another example of a trademark front-runner losing, and of a panelist indicating that applicants need some kind of bad faith in order to lose and LRO.

.home (Defender Security Company v. DotHome Inc.)

Kicked out for the same reasons as the other Defender objections to rival .home — it was a transparent gaming attempt based on a flimsy, recently acquired trademark. See here and here.

DotHome Inc is the subsidiary Directi/Radix is using to apply for .home.

The decision (pdf) goes into a bit more detail than the other .home decisions we’ve seen to date, including information about how much Defender paid to acquire its trademarks ($75,000) and how many domains its bogus Go Daddy reseller site has sold (three).

.home (Defender Security Company v. Baxter Pike)

Ditto. This time the applicant was a Donuts subsidiary.

.song (DotMusic Limited v. Amazon)

Like the failed .home objections, the .song objection was based on a trademark acquired tactically in late 2012 by Constantine Roussos, whose company, CGR E-Commerce, is applying for .music.

This objection failed (pdf) for the same reasons as the same company’s objection to Amazon’s .tunes application failed last week — a trademark for “.SONG” is simply too generic and descriptive to give DotMusic exclusive rights to the matching gTLD.

Roussos has also filed seven LROs against his competitors for .music, none of which have yet been decided.

.gmbh (TLDDOT GmbH v. InterNetWire Web-Development)

Both objector and respondent here are applicants for .gmbh, which indicates limited liability companies in German-speaking countries.

TLDDOT registered its European trademark in “.gmbh” a few years ago.

Despite the fact that it was obviously acquired purely in order to secure the matching gTLD, the panelist in this case ruled that it was bona fide.

Despite this, the panelist concluded that for InternetWire to operate .gmbh in the generic, dictionary-word sense outlined in its application would not infringe these trademark rights.

What some other bloggers said about .amazon

Whenever an ICANN decision intersects with the business interests of a well-known brand name, media coverage ensues, and last week’s Governmental Advisory Committee objection to .amazon was no exception.

While a scores of headlines were generated, there wasn’t a great deal of editorializing or analysis. Most bloggers outside of the domain industry seemed content to link to and summarize a Wall Street Journal report.

But a handful of bloggers also passed comment on the decision. Views were a diverse as you might expect. Here are a few selections:

Geoffrey Manne of Truth On The Market was not impressed with what the decision said about ICANN as a regulator. He wrote:

If Latin American governments are concerned with cultural and national identity protection, they should (not that I’m recommending this) focus their objections on Amazon.com. But the reality is that Amazon.com doesn’t compromise cultural identity, and neither would Amazon’s ownership of .AMAZON.

Brand Aide called Amazon a “brand bully” and recounted a client’s past experience:

For years now, Amazon’s attorneys would have one think the Amazon River never existed. A number of years ago, one of my firm’s clients was sued by Amazon over use of the “Amazon Networks” in a domain for computer services, a term our client innocently registered about the same time Amazon launched as a bookseller. Amazon falsely claimed in federal court our client was a domain cybersquatter. In fact, the homepage of our client’s first website featured an image of the Amazon River.

Hot Hardware empathized with the GAC:

These countries make a good point. It may seem obvious that Amazon.com would get a crack at .amazon, but many in the U.S. would be upset if, say, a German company laid claim to .grandcanyon or another important U.S. geological site.

Retail trade pub Storefront Talkback sided with Amazon:

what initially looked like just a very expensive way to acquire their own .brand names is now turning into a process that’s effectively stripping some chains of their brands.

Geek.com didn’t like .amazon as a string anyway:

I also think this decision is doing Amazon a favor. .amazon is a bit long for the end of a URL. The company would be better off using a shortened version such a .amzn, it’s quicker to type and looks better when paired with categories, e.g. dvd.amzn, bluray.amzn, ebooks.amzn.

WebProNews perhaps misses the point about geographic names a bit in its speculation about .apple:

It’s going to be interesting to see if Apple meets a similar fate to Amazon. It only applied for one gTLD – .apple. Like Amazon, the word apple isn’t exclusive to the company. I find it hard to believe that ICANN would hand Apple exclusive control of the .apple gTLD, but it’s possible.

Finally, book publisher Melville House said on its blog:

The principle the South American nations are referring to is, as I understand it, a little known agreement from the early days of Arpanet that in the case of a governmental disagreement, anyone who could best a region’s most dangerous wildlife in unarmed combat was welcome to that region’s domain name. The protocol hasn’t often been used since the gory events of June 1998, when one intrepid developer hoped to claim .yukon for his online baked potato delivery service.

Patagonia was similarly denied their request for .patagonia last week, after a company representative found himself facing down the pointy end of a condor.

Senators slate NTIA, to demand answers on new gTLD security

Did Verisign get to the US Congress? That’s the intriguing question emerging from a new Senate appropriations bill.

In notes attached to the bill, the Senate Appropriations Committee delivers a brief but scathing assessment of the National Telecommunication and Information Administration’s performance on ICANN’s Governmental Advisory Committee.

It says it believes the NTIA has “not been a strong advocate for U.S. companies and consumers”.

The notes would order the agency to appear before the committee within 30 days to defend the “security” aspects of new gTLDs and “urges greater participation and advocacy within the GAC”.

While the NTIA had a low-profile presence at the just-finished Durban meeting, it would be difficult to name many other governments that participate or advocate more on the GAC.

This raises an eyebrow. Which interests, in the eyes of the committee, is the NTIA not sufficiently defending?

Given the references to intellectual property, suspicions immediately fall on usual suspects such as the Association of National Advertisers, which is worried about cybersquatting and associated risks.

The ANA successfully lobbied for an ultimately fruitless Congressional hearing in late 2011, following its campaign of outrage against the new gTLD program.

It’s mellowed somewhat since, but still has fierce concerns. Judging by comments its representatives made in Durban last week, it has shifted its focus to different security issues and is now aligned with Verisign.

Verisign, particularly given the bill’s reference to “security, stability and resiliency” and the company’s campaign to raise questions about the potential security risks of new gTLDs, is also a suspect.

“Security, stability and resiliency” is standard ICANN language, with its own acronym (SSR), rolled out frequently during last week’s debates about Verisign’s security concerns. It’s unlikely to have come from anyone not intimately involved in the ICANN community.

And what of Amazon? The timing might not fit, but there’s been an outcry, shared by almost everyone in the ICANN community, about the GAC’s objection last week to the .amazon gTLD application.

The NTIA mysteriously acquiesced to the .amazon objection — arguably harming the interests of a major US corporation — largely it seems in order to play nice with other GAC members.

Here’s everything the notes to “Departments of Commerce and Justice, and Science, and related agencies appropriations Bill, 2014” (pdf) say about ICANN:

ICANN — NTIA represents the United States on the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers [ICANN] Governmental Advisory Committee [GAC], and represents the interests of the Nation in protecting its companies, consumers, and intellectual property as the Internet becomes an increasingly important component of commerce. The GAC is structured to provide advice to the ICANN Board on the public policy aspects of the broad range of issues pending before ICANN, and NTIA must be an active supporter for the interests of the Nation. The Committee is concerned that the Department of Commerce, through NTIA, has not been a strong advocate for U.S. companies and consumers and urges greater participation and advocacy within the GAC and any other mechanisms within ICANN in which NTIA is a participant.

NTIA has a duty to ensure that decisions related to ICANN are made in the Nation’s interest, are accountable and transparent, and preserve the security, stability, and resiliency of the Internet for consumers, business, and the U.S. Government. The Committee instructs the NTIA to assess and report to the Committee within 30 days on the adequacy of NTIA’s and ICANN’s compliance with the Affirmation of Commitments, and whether NTIA’s assessment of ICANN will have in place the necessary security elements to protect stakeholders as ICANN moves forward with expanding the number of top level Internet domain names available.

While the bill is just a bill at this stage, it seems to be a strong indication that anti-gTLD lobbyists are hard at work on Capitol Hill, and working on members of diverse committees.

Recent Comments