ICANN apologizes to “arms dealer” claim security firm after email goes missing

ICANN has apologized to the security company that claimed an accredited registrar was in league with malware distributors, after an email went AWOL.

You may recall that registrar GalComm was accused by Awake Security last month of turning a blind eye to abuse in a report entitled “The Internet’s New Arms Dealers: Malicious Domain Registrars” and that ICANN’s preliminary investigation later essentially dismissed the allegations.

ICANN had told GalComm (pdf) August 18 that Awake had not “to date” contacted ICANN about its allegations, but that appears to have been untrue.

GalComm’s lawyers had in fact emailed a letter to ICANN, using its “globalsupport” at icann.org email address, on August 6, as said lawyers testily informed (pdf) Global Domains Division VP Russ Weinstein August 20.

Weinstein has now confirmed (pdf) that a letter from Awake was received to said email address but “was not escalated internally”. He said he was “previously unaware” of the letter. He wrote:

I apologize for this inadvertent oversight and we will use this as a training opportunity to prevent such errors in the future.

GalComm has been threatening to sue Awake for defamation since the “arms dealer” report was published, so it looks like ICANN’s decision to eat humble pie is probably a prudent way to keep its name off the docket.

The letter from Awake’s lawyers (pdf) also includes a lengthy explanation of why the original report is not, in its view, defamatory.

The lesson for the rest of us appears to be that the ICANN email address in question is probably not the best way to reach ICANN’s senior management.

Weinstein said that abuse complaints about registrars should be sent to its “compliance” at icann.org address.

Amazon waves off demand for more government blocks

Amazon seems to have brushed off South American government demands for more reserved domains in the controversial .amazon gTLD.

VP of public policy Brian Huseman has written to Amazon Cooperation Treaty Organization secretary general Alexandra Moreira to indicate that Amazon is pretty much sticking to its guns when it comes to .amazon policy.

Moreira had written to Huseman a few weeks ago to complain that the Public Interest Commitments included in Amazon’s registry contract with ICANN do not go far enough to protect terms culturally sensitive to the Amazon region.

She wanted more protection for the “names of cities, villages, mountains, rivers, animals, plants, food and other expressions of the Amazon biome, biodiversity, folklore and culture”.

ACTO also has beef with an apparently unilateral “memorandum of understanding” (page 8 of this PDF) Amazon says it has committed to.

That MoU would see the creation of a Steering Committee, comprising three Amazon representatives and nine from ACTO and each of its eight member states, which would guide the creation and maintenance of .amazon block-lists.

ACTO is worried that the PICs make no mention of either the committee or the MoU, and that Huseman is the only signatory to the MoU, which it says makes the whole thing non-binding.

Moreira’s August 14 letter asked for Amazon and ACTO to “mutually agree on a document”, and for the PICs to be amended to incorporate the MoU, making it binding and enforceable. She also asked for potentially thousands of additional protected terms.

Huseman replied August 28, in a letter seen by DI, to say that Amazon is “committed to safeguard the people, culture, and heritage of the Amazonia region” and that the PICs and MoU “have the full backing and commitment” of the company.

He added:

We are disappointed that we have not yet received the names and contact information of those within ACTO who might serve on the Steering Committee contemplated in the MOU because their knowledge and help could be very beneficial as we move forward to implement the PICs.

The letter does not address ACTO’s demand for a binding bilateral agreement, nor the request for additional blocks.

ICANN itself is no longer a party to these negotiations, having washed its hands of the sorry business last month.

Schreiber really did sue you all, sorry

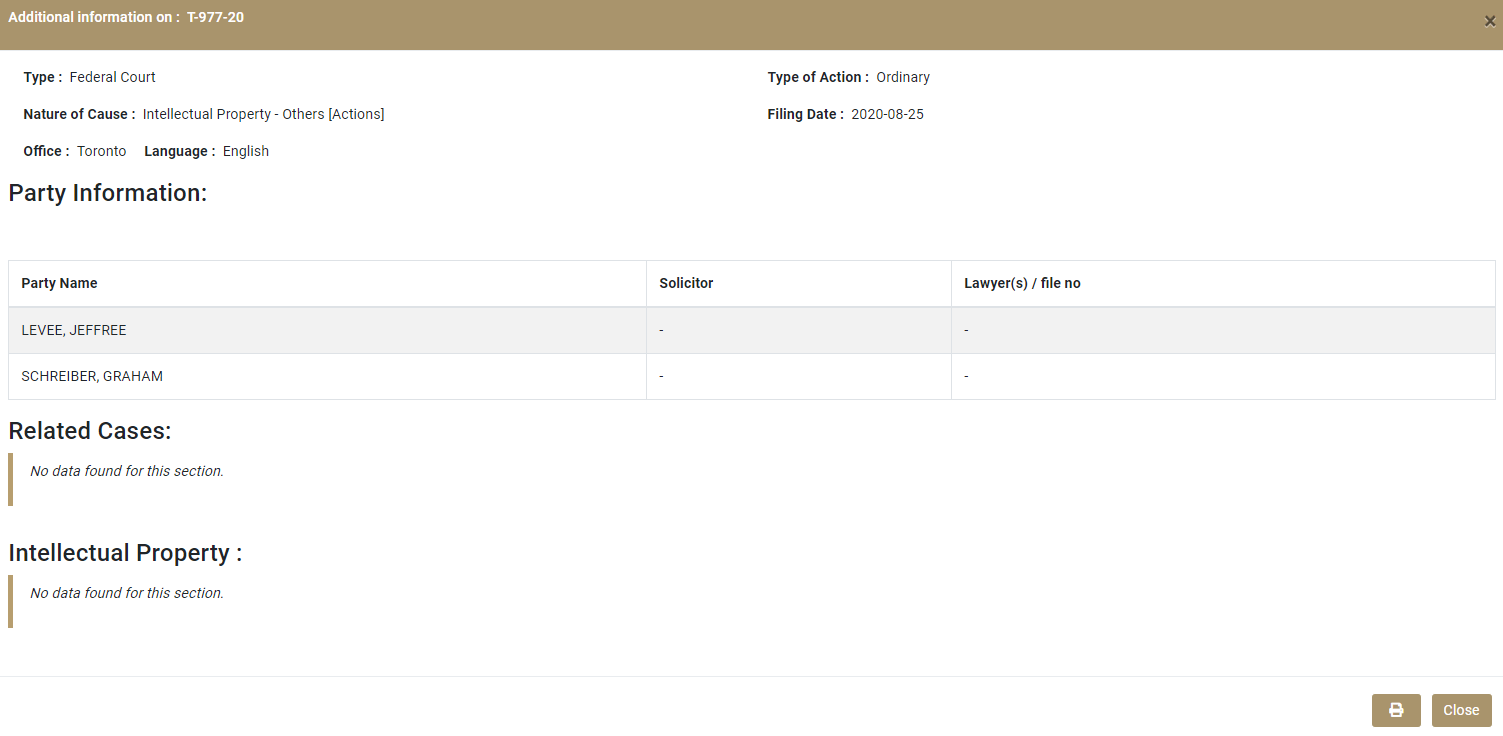

It seems the aggrieved domain registrant and troll Graham Schreiber really has filed a lawsuit against scores of current and former domain name industry and ICANN community members.

You may recall that last week I blogged about a purported lawsuit by Schreiber against many industry professionals, as well as people who’ve been heavily involved in ICANN over the last couple decades.

I noted that there was no independent confirmation that any complaint has actually been filed in any court, but it turns out a complaint has now actually been filed.

A search on the Canadian Federal Court system reveals:

That appears to be an intellectual property lawsuit filed August 25 by Schreiber against “Jeffrey Levee et al”.

That’s five days after the document started circulating among defendants and my original coverage.

Levee is the long-time outside counsel for ICANN, working for Jones Day for two decades. In the org’s early days, his name often popped up in conspiracy theories.

The Schreiber document that was circulated last week just happened to name Levee as his first defendant, followed by several dozen more, often far less influential, individuals and companies.

To see my original coverage of the pretty much incomprehensible complaint, along with a link to the document, go here.

Fight over closed generics ends in stalemate

Closed generic gTLDs could be a thing in the next application round. Or they might not. Even after four years, ICANN’s greatest policy-making minds can’t agree.

The New gTLDs Subsequent Procedures working group (SubPro) delivered its draft final policy recommendations last week, and the most glaring lack of consensus concerned closed generics.

A closed generic is a dictionary-word gTLD, not matching the applicant’s trademark, that is nevertheless treated as if it were a dot-brand, where the registry is the only eligible registrant.

It’s basically a way for companies to vacuum up the strings most relevant to their businesses, keeping them out of the hands of competitors.

There were 186 attempts to apply for closed generics in 2012 — L’Oreal applied for TLDs such as .beauty, .makeup and .hair with the clear expectation of registry-exclusive registrations, for example

But ICANN moved the goalposts in 2013 following advice from its Governmental Advisory Committee, asking these applicants to either withdraw or amend their applications. It finally banned the concept in 2015, and punted the policy question to SubPro.

But SubPro, made up of a diverse spectrum of volunteers, was unable to reach a consensus on whether closed generics should be allowed and under what circumstances. It’s the one glaring hole in its final report.

The working group does appear to have taken on board the same GAC advice as ICANN did seven years ago, however, which presents its own set of problems. Back in 2013, GAC advice was often written in such a way as to be deliberately vague and borderline unimplementable.

In this case, the GAC had told ICANN to ban closed generics unless there was a “a public interest goal”. What to make of this advice appears to have been a stumbling block for SubPro. What the hell is the “public interest” anyway?

Working group members were split into three camps: those that believed closed generics should be banned outright, those who believed that should be permitted without limitation, and those who said they should be allowed but tightly regulated.

Three different groups from SubPro submitted proposals for how closed generics should be handled.

The most straightforward, penned by consultant Kurt Pritz and industry lawyers Marc Trachtenberg and Mike Rodenbaugh, and entitled The Case for Delegating Closed Generics (pdf) basically says that closed generics encourage innovation and should be permitted without limitation.

This trio argues that there are no adequate, workable definitions of either “generic” or “public interest”, and that closed generics are likely to cause more good than harm.

They raise the example of .book, which was applied for by Amazon as a closed generic and eventually contracted as an open gTLD.

Many of us were thrilled when Amazon applied for .book. Participation by Amazon validated the whole program and the world’s largest book seller was well disposed to use the platform for innovation. Yet, we decided to get in the way of that. What harm was avoided by cancelling the incalculable benefit staring us right in the face?

Coincidentally, Amazon signed its .book registry agreement exactly five years ago today and has done precisely nothing with it. There’s not even a launch plan. It looks, to all intents and purposes, warehoused.

It goes without saying that if closed generics are allowed by ICANN, it will substantially increase the number of potential new gTLD applicants in the next round and therefore the amount of work available for consultants and lawyers.

The second proposal (pdf), submitted by recently independent policy consultant Jeff Neuman of JJN Solutions, envisages allowing closed generics, but with only with heavy end-user (not registrant) involvement.

This idea would see a few layers of oversight, including a “governance council” of end users for each closed generic, and seems to be designed to avoid big companies harming competition in their industries.

The third proposal (pdf), written by Alan Greenberg, Kathy Kleiman, George Sadowsky and Greg Shatan, would create a new class of gTLDs called “Public Interest Closed Generic gTLDs” or “PICGS”.

This is basically the non-profit option.

PICGS would be very similar to the “Community” gTLDs present since the 2012 round. In this case, the applicant would have to be a non-profit entity and it would have to have a “critical mass” of support from others in the area of interest represented by the string.

The model would basically rule out the likes of L’Oreal’s .makeup and Amazon’s .book, but would allow, off the top of my head, something like .relief being run by the likes of the Red Cross, Oxfam and UNICEF.

Because the working group could not coalesce behind any of these proposals, it’s perhaps an area where public comment could have the most impact.

The SubPro draft final report is out for public comment now until September 30.

After it’s given final approval, it will go to the GNSO Council and then the ICANN board before finally becoming policy.

New gTLD prices could be kept artificially high

ICANN might keep its new gTLD application fees artificially expensive in future in order to deter TLD warehousing.

Under a policy recommendation out from the New gTLDs Subsequent Procedures working group (SubPro) last week, ICANN should impose an “application fee floor” to help keep top-level domains out of the hands of gamers and miscreants.

In the 2012 application round, the $185,000 fee was calculated on a “cost-recovery basis”. That is, ICANN was not supposed to use it as a revenue source for its other activities.

But SubPro wants to amend that policy so that, should the costs of the program ever fall before a yet-to-be-determined minimum threshold, the application fee would be set at this fee floor and ICANN would take in more money from the program than it costs to run.

SubPro wrote:

The Working Group believes that it is appropriate to establish an application fee floor, or minimum application fee that would apply regardless of projected program costs that would need to be recovered through application fees collected. The purpose of an application fee floor is to deter speculation and potential warehousing of TLDs, as well as mitigate against the use of TLDs for abusive or malicious purposes. The Working Group’s support for a fee floor is also based on the recognition that the operation of a domain name registry is akin to the operation of a critical part of the Internet infrastructure.

The working group did not put a figure on what the fee floor should be, instead entrusting ICANN to do the math (and publicly show its working).

But SubPro agreed that ICANN should not use what essentially amounts to a profit to fund its other activities.

The excess cash could only be used for things related to the new gTLD program, such as publicizing the availability of new gTLDs or subsidizing poorer applicants via the Applicant Support Program.

ICANN already accounts for its costs related to the program separately. It took in $361 million in application fees back in 2012 and as of the end of 2019 it had $62 million remaining.

Does that mean fees could come down by as much as 17% in the next application round based on ICANN’s experience? Not necessarily — about a third of the $185,000 fee was allocated to a “risk fund” used to cover unexpected developments such as lawsuits, and that risk profile hasn’t necessarily changed in the last eight years.

Fees could be lowered for other reasons also.

As I blogged earlier today, a new registry service provider pre-evaluation program could reduce the application fee for the vast majority of applicants by eliminating redundancies and shifting the cost of technical evaluations from applicants to RSPs.

The financial evaluation is also being radically simplified, which could reduce the application fee.

In 2012, evaluations were carried out based on the applicant’s modelling of how many domains it expected to sell and how that would cover its expenses, but many applicants were way off base with their projections, rendering the process flawed.

SubPro proposes to do away with this in favor generally of applicants self-certifying that their financial situation meets the challenge. Public companies on the world’s largest 25 exchanges won’t have to prove they’re financially capable of running a gTLD at all.

The working group is also proposing changes to the Applicant Support Program, under which ICANN subsidizes the application fee for needy applicants. It wasn’t used much in 2012, a failure largely attributed to ICANN’s lack of outreach in the Global South.

Under SubPro’s recommendations, ICANN would be required to do a much better job of advertising the program’s existence, and subsidies would extend beyond the application fee to additional services such as consultants and lawyers.

Language from the existing policy restricting the program to a few dozen of the world’s poorest countries (which was, in practice, ignored in 2012 anyway), would also be removed and ICANN would be encouraged to conduct outreach in a broader range of countries.

In terms of costs, dot-brand applicants also get some love from SubPro. These applicants will be spared the requirement to have a so-called Continuing Operations Instrument.

The COI is basically a financial safeguard for registrants, usually a letter of credit from a big bank. In the event that a registry goes out of business, the COI is tapped to pay for three years of operations, enabling registrants to peacefully transition to a different TLD.

Given that the only registrant of a dot-brand gTLD is the registry itself, this protection clearly isn’t needed, so SubPro is making dot-brand applicants exempt.

Overall, it seems very likely that the cost of applying for a new gTLD is going to come down in the next round. Whether it comes down to something in excess of the fee floor or below it is going to depend entirely on ICANN’s models and estimates over the coming couple of years.

New back-end approval program could reduce the cost of a new gTLD

ICANN will consider a new pre-approval program for registry back-end service providers in order to streamline the new gTLD application process and potentially reduce application fees.

The proposed “RSP pre-evaluation process” was one of the biggest changes to the new gTLD program agreed to by ICANN’s New gTLDs Subsequent Procedures working group (SubPro), which published its final report for comment last week.

The recommendation addresses what was widely seen as a huge process inefficiency in the evaluation phase of the 2012 application round, which required each application to be subjected to a unique technical analysis by a team of outside experts.

This was perceived as costly, redundant and wasteful, given that the large majority of applications proposed to use the same handful of back-end RSPs.

Donuts, which applied for over 300 strings with virtual cookie-cutter business models and all using the same back-end, had to pay for over 300 technical evaluations, for example.

Similarly, clients of dot-brand service providers such as Neustar and Verisign each had to pay for the same evaluation as hundreds of fellow clients, despite the tech portions of the applications being largely copy-pasted from the same source.

For subsequent rounds, that will all change. ICANN will instead do the tech evals on a per-RSP, rather than per-application, basis.

All RSPs that intend to fight for business in the next round will undergo an evaluation before ICANN starts accepting applications. In a bit of a marketing coup for the RSPs, ICANN will then publish the names of all the companies that have passed evaluation.

The RSPs would have to cover the cost of the evaluation, and would have to be reevaluated prior to each application window. ICANN would be banned from making a profit on the procedure.

SubPro agreed that applicants selecting a pre-approved RSP should not have to pay the portion of the overall application fee — $185,000 in 2012 — that covers the tech eval.

RSPs may decide to recoup the costs from their clients via other means, of course, but even then the fee would be spread out among many clients.

The proposed policy, which is still subject to SubPro, GNSO Council and ICANN board approval, is a big win for the back-ends.

Not only do they get to offer prospective clients a financial incentive to choose them over an in-house solution, but ICANN will also essentially promote their services as part of the program’s communications outreach. Nice.

Single/plural gTLD combos to be BANNED

Singular and plural versions of the same string will be banned at the top level under proposed rule changes for the next round of new gTLDs.

The final set of recommendations of ICANN’s New gTLDs Subsequent Procedures working group (SubPro), which were published after four years of development last week, state:

the Working Group recommends prohibiting plurals and singulars of the same word within the same language/script in order to reduce the risk of consumer confusion. For example, the TLDs .EXAMPLE and .EXAMPLES may not both be delegated because they are considered confusingly similar.

The 2012 round had no hard and fast rule about plurals. There were String Similarity Review and String Confusion Objection procedures, but they produced unpredictable results.

At least 15 single/plural string pairs currently exist in the root, including .fan(s), .accountant(s), .loan(s), .review(s) and .deal(s). Sometimes they’re both part of the same registry’s portfolio, other times they’re owned by competitors.

But others, including .pet and .pets and .sport and .sports, were ruled by independent panels too “confusingly similar” to be allowed to coexist.

The proposed new rule would remove much of the subjectivity from these kinds of decisions, replacing the current system of objections with a flat no-coexistence rule.

If a gTLD that was the plural of an existing gTLD were applied for, the application would be rejected. If the singular and plural variants of the same word were applied for in the same round, the applications would likely end up at auction.

But there would be some wriggle room, with the ban only applying if both applied-for strings truly are singular/plural variations of each other in the same language. The working group wrote:

.SPRING and .SPRINGS could both be allowed if one refers to the season and the other refers to elastic objects, because they are not singular and plural versions of the same word. However, if both are intended to be used in connection with the elastic object, then they will be placed into the same contention set. Similarly, if an existing TLD .SPRING is used in connection with the season and a new application for .SPRINGS is intended to be used in connection with elastic objects, the new application will not be automatically disqualified.

In such situations, both registries would have to agree to binding Public Interest Commitments to only use the gTLDs for their stated, non-conflicting purposes. Registrants would also have to commit to only use .spring to represent the season and .springs for the elastic objects, also.

The ban will substantially eliminate the problem I’ve previously referred to as “tailgating”, where a registry applies for the plural variant of a competitor’s successful, well-marketed gTLD, prices domains slightly lower, then sits back to effortlessly reap the benefits of their rival’s popularity.

One could easily imagine applicants for strings such as .clubs or .sites in the next round, with applicants content to lazily ride the coat-tails of the million-selling singular namespaces.

The rule change will also remove the need for existing registries to defensively apply for the single/plural variants of their current portfolio, and for existing registrants to be compelled to defensively registry domains in yet another TLD.

On the flipside, it means that some potentially useful strings would be forever banned from the DNS.

While it might make sense for a film producer to register a .movie domain to market a single movie, it would not make sense for a review site or movies-related blog, where a .movies domain would be more appropriate. But now that’s never going to be possible.

SubPro’s work is still subject to final approval by SubPro, the GNSO Council and ICANN board of directors before it becomes policy.

ICANN might pay for your lockdown broadband

ICANN is to seriously consider requests that community volunteers should have their broadband costs subsidized out of the ICANN budget.

On Thursday, its board of directors will meet to discuss what it’s calling the “ICANN Pandemic Internet Access Reimbursement Program Pilot”.

No additional information is currently available, but the name of the proposed pilot is pretty descriptive.

The agenda item follows calls from some community members for ICANN to help out with the costs of broadband (and potentially hotel rooms) for those who have incurred out-of-pocket expenses to participate in ICANN’s remote Zoom meetings.

ICANN typically covers the travel and accommodation for certain key policy-making volunteers attending its thrice-yearly public meetings and occasional intersessional face-to-face gatherings.

With coronavirus confining most of these people to their home offices for the last several months, and with all official ICANN meetings going virtual, ICANN could save as much as $8 million this calendar year

Paying the broadband costs of a handful of community members would likely amount to a mere drop in that ocean.

However, while the details of the proposed pilot program are not yet known, one could imagine how galling it would be to many if ICANN opened its piggy-bank to North American lawyers on six-figure salaries, rather than only to volunteers from the broadband-poor developing world.

As a reminder, ICANN’s budget primarily comes from the “tax” registrants pay whenever they register a gTLD domain name.

Still, we shouldn’t prejudge these things. Perhaps the policy will be sensible.

ICANN introduced a similar pilot reimbursement program for community members with childcare needs last year, largely without controversy. Due to the absence of face-to-face meetings this year, this cash-for-kids scheme will run until ICANN 71 in June next year.

The end of the beginning? ICANN releases policies for next round of new gTLDs

Over eight years after ICANN last accepted applications for new gTLDs and more than four years after hundreds of policy wonks first sat around the table to discuss how the program could be improved, the working group has published its draft final, novel-length set of policy recommendations.

Assuming the recommendations are approved, in broad terms the next round will be roughly similar to the 2012 round.

But almost every phase of the application process, from the initial communications program to objections and appeals, is going to get tweaked to a greater or lesser extent.

The recommendations came from the GNSO’s New gTLD Subsequent Procedures working group, known as SubPro. It had over 200 volunteer members and observers and worked for thousands of hours since January 2016 to come up with its Final Draft Report.

Some of the proposed changes mean the cost of an application will likely go down, while others will keep the cost artificially high.

Some changes will streamline the application process, others may complicate it.

Many of the “changes” to policy are in fact mere codifications of practices ICANN brought in unilaterally under the controversial banner of “implementation” in the 2012 round.

Essentially, the GNSO will be giving the nod retroactively to things like Public Interest Commitments, lottery-based queuing, and name collisions mitigation, which had no basis in the original new gTLDs policy.

But other contentious aspects of the last round are still up in the air — SubPro failed to find consensus on highly controversial items such as closed generics.

The report will not tell you when the next round will open or how much it will cost applicants, but the scope of the work ahead should make it possible to make some broad assumptions.

What it will tell you is that the application process will be structurally much the same as it was eight years ago, with a short application window, queued processing, objections, and contention resolution.

SubPro thankfully rejected the idea replacing round-based applications with a first-come, first-served model (which I thought would have been a gaming disaster).

The main beneficiaries of the policy changes appear to be registry service providers and dot-brand applicants, both of which are going to get substantially lowered barriers to entry and likely lower costs.

There are far too many recommendations for me to summarize them eloquently in one blog post, so I’m going to break up my analysis over several articles to be published over the next week or so.

In the meantime, ICANN has opened up the final draft report for public comment. You have until September 30.

The report notes that previously rejected comments will not be considered, so if your line is “New gTLDs suck! .com is King!” you’re likely to find your input falling on deaf ears.

After the comment period ends, and SubPro considers the comments, the report will be submitted to the GNSO Council for approval. Subsequently, it will need to be approved by the ICANN board of directors.

It’s not impossible that this could all happen this year, but there’s a hell of a lot of implementation work to be done before ICANN starts accepting applications once more. We could be looking at 2023 before the next window opens and 2024 before the next batch of new gTLDs start to launch.

UPDATE: This post was updated August 27, 2020 to clarify procedural and timing issues.

It’s a CONSPIRACY! Canadian registrant “sues” pretty much everybody

Canadian domain registrant and noted industry troll Graham Schreiber has sued, or at least claims to have sued, just about every notable figure in the ICANN community.

A document purporting to be a lawsuit is being circulated today among some of the dozens of named defendants, which include several people who’ve not been involved with ICANN for many years.

It names 27 volunteers from ICANN’s Intellectual Property Constituency, 21 current and former senior executives of registries and registrars, several members of the US and UK governments, an FBI agent, an unnamed “White House Conspirator”, as well as lawyers for LinkedIn, Facebook, Twitter, ICANN, Google and the UK Intellectual Property Office.

It’s my job to tell you in simple terms what the alleged lawsuit alleges, but I’m afraid I’m at an utter loss with this one. It reads like the fever dream of a conspiracy theorist that would make the average Qanon believer appear the model of reason and clarity.

Schreiber variously refers to his defendants as “Kingpins” involved in a “Cartel” or “Conspiracy”, the factual details of which he never quite gets to.

Here’s a representative sample paragraph, unedited:

If and when, the “Defensive Registrations” obliged by ICANN’s R[r]egistry & R[r]egistrar “Stakeholders” = “Kingpins” and specifically CentralNic [ weren’t purchased ] assailants would strike; and Infringe, Dilute, Blur and Pass-Off as our online business, individually with identical and confusingly similar domain name, faking to be appointed or an authorized agent of the primary Registrant, in a country’s entrepreneurs Intellectual Property may or may not have been protectable at Common Law Trademark, under Madrid Protocol Rules, as it / they fulfilled the obligations of local National laws, to become a Registered Trademark, as I secured in the USA with USPTO, after the CIPO did their work.

At one point, he admits to trolling the defendants on social media since 2012, and points to their failure to sue him as evidence of a conspiracy:

I’ve made statements via those Social Media resources which would, if they were untrue, subject me to a singular lawsuit or multiple lawsuits from the Defendants listed, for: Defamation, Slander and Libel.

As yet, these well taunted Defendants have all conspired together, in collective silence, anticipating that their grandeur and my insignificance would, maintain safe passage, for them to continue.

As the vast majority of the Defendants are well schooled, powerful U.S. Attorneys, it’s my expectation that the Court oblige them to address the charges here stated, or collectively for their defence, they must File a lawsuit with this Court, charging me for what could be [ but aren’t ] remarks constituting Defamation, Slander & Libel against them, which again, I’ve posted on some of the Defendants own clients, Social Media Platforms

Schreiber was once a regular fixture in DI’s comments section too. Thankfully, we’ve not heard from him in years.

The root cause of the “lawsuit” appears to be an old beef Schreiber has with CentralNic.

He says he owns what he calls a “common law trademark” on the term “Landcruise” and he once used the matching .com domain to operate a motor-home rental business.

At some point in 2011, he became aware that a British registrant had registered landcruise.co.uk and landcruise.uk.com.

At the time, CentralNic was primarily in the business of selling domains at the third level in pseudo-gTLDs such as uk.com, gb.com and us.com.

Schreiber tried and failed (twice) to get the .uk domain transferred under Nominet’s Dispute Resolution Service, and then he took his beef to the courts.

In 2012, he sued CentralNic, ICANN, Verisign, eNom, and Network Solutions in a complaint that barely made much more sense than the “lawsuit” being circulated today.

That case was thrown out of court in 2013.

I expect the same fate to befall the current lawsuit, if indeed it has even been filed in a court.

Schreiber wants $5 million from every defendant.

If you want to check whether you’re one of them, read the PDF “complaint” here.

Recent Comments