ICANN compliance not broken, Ombudsman rules

Ombudsman Chris LaHatte has rejected a complaint from spam research firm KnujOn — and 173 of its supporters — claiming that ICANN’s compliance department is failing consumers.

In a ruling posted online today, LaHatte said there was “no substance” to complaints that a small number of “bad” registrars, notably BizCN, have been allowed to run wild.

KnujOn’s Garth Bruen is a regular and vocal critic of ICANN compliance, often claiming that it ignores complaints about bad Whois data and fails to enforce the Registrar Accreditation Agreement, enabling fake pharma spamming operations to run from domains sponsored by ICANN-accredited registrars.

This CircleID blog post should give you a flavor.

The gist of the complaint was that ICANN regularly fails to enforce the RAA when registrars allow bad actors to own domain names using plainly fake contact data.

But LaHatte ruled, based on a close reading of the contracts, that the Bruen and KnujOn’s supporters have overestimated registrars’ responsibilities under the RAA. He wrote:

the problem is that the complainants have overstated the duties of the registrar, the registrant and the role of compliance in this matrix.

He further decided that allegations about ICANN compliance staff being fired for raising similar issues were unfounded.

It’s a detailed decision. Read the whole thing here.

First URS case decided with Facebook the victor

Facebook has become the first company to win a Uniform Rapid Suspension complaint.

The case, which dealt with the domain facebok.pw, took 37 days from start to finish.

This is what the suspended site now looks like:

The URS was designed for new gTLDs, but .PW Registry decided to adopt it too, to help it deal with some of the abuse it started to experience when it launched earlier this year.

Facebook was the first to file a complaint, on August 21. According to the decision, the case commenced about three weeks later, September 11, and was decided September 26.

I don’t know when the decision was published, but World Trademark Review appears to have been the first to spot it.

It was pretty much a slam-dunk, uncontroversial decision, as you might imagine given the domain. The standard is “clear and convincing evidence”, a heavier burden than UDRP.

The registrant did not respond to the complaint, but Facebook provided evidence showing he was a serial cybersquatter.

The decision was made by the National Arbitration Forum’s Darryl Wilson, who has over 100 UDRP cases under his belt. Here’s the meat of it:

IDENTICAL OR CONFUSINGLY SIMILAR

The only difference between the Domain Name, facebok.pw, and the Complainant’s FACEBOOK mark is the absence of one letter (“o”) in the Domain Name. In addition, it is well accepted that the top level domain is irrelevant in assessing identity or confusing similarity, thus the “.pw” is of no consequence here. The Examiner finds that the Domain Name is confusingly similar to Complainant’s FACEBOOK mark.

NO RIGHTS OR LEGITIMATE INTERESTS

To the best of the Complainant’s knowledge, the Respondent does not have any rights in the name FACEBOOK or “facebok” nor is the Respondent commonly known by either name. Complainant has not authorized Respondent’s use of its mark and has no affiliation with Respondent. The Domain Name points to a web page listing links for popular search topics which Respondent appears to use to generate click through fees for Respondent’s personal financial gain. Such use does not constitute a bona fide offering of goods or services and wrongfully misappropriates Complainant’s mark’s goodwill. The Examiner finds that the Respondent has established no rights or legitimate interests in the Domain Name.

BAD FAITH REGISTRATION AND USE

The Domain Name was registered and is being used in bad faith.

The Domain Name was registered on or about March 26, 2013, nine years after the Complainant’s FACEBOOK marks were first used and began gaining global notoriety.

The Examiner finds that the Respondent has engaged in a pattern of illegitimate domain name registrations (See Complainant’s exhibit URS Site Screenshot) whereby Respondent has either altered letters in, or added new letters to, well-known trademarks. Such behavior supports a conclusion of Respondent’s bad faith registration and use. Furthermore, the Complainant submits that the Respondent is using the Domain Name in order to attract for commercial gain Internet users to its parking website by creating a likelihood of confusion as to the source, sponsorship or affiliation of the website. The Examiner finds such behavior to further evidence Respondent’s bad faith registration and use.

The only remedy for URS is suspension of the domain. According to Whois, it still belongs to the respondent.

Read the decision in full here.

Register.com hit by breach notice over 62,232 domains

Register.com, a Web.com business that is one of the top ten registrars by domains under management, has been hit by an ICANN compliance notice covering 62,232 domain names.

It’s a weird one.

ICANN says that the company has failed to provide records documenting the ownership trail of the domains in question, which all currently belong to Register.com itself.

The notice names 000123.net, 0011pp.com, 00h4.com, 010fang.net, 01rabota.com, 02071988.com and 020tong.com, but it seems that these are merely the first in a alphabetical list that is much, much longer.

Judging by DomainTools’ Whois history, these domains all appear to have been originally registered at various times by individuals in China and India, then allowed to expire, then registered by Register.com to itself.

The only common link appears to be that they were kept by Register.com after they expired, for whatever reasons registrars usually hoard their customers’ expired domains.

According to the compliance notice, ICANN wants the registrar to:

Provide a detailed explanation to ICANN how 62,232 domains in which Register.com itself is the registrant are used for the purposes of Registrar Services, as defined by Section 1.11 of the RAA;

The Registrar Accreditation Agreement says registrars have to keep registrant agreement records, except for a limited class of cases where the domain is owned by the registrar itself and used for registrar-related stuff.

Register.com, one of the original five oldest competitive registrars, has been given until October 2 to come up with the requested information for face losing its accreditation.

The registrar has almost three million gTLD domains under management. Combined with its Web.com sister registrars, which include Network Solutions, the number is closer to 10 million.

Registrar rapped for failing to transfer UDRP domain

The domain name registrar Gal Comm has been warned by ICANN that it risks losing its accreditation for failing to transfer a cybersquatted name to Home Depot.

The compliance notice (pdf) concerns the domain name homedpeot.com, which was lost in a UDRP filed in early March and decided on April 21.

According to ICANN, Gal Comm, which has about 30,000 gTLD domains under management, failed to transfer the domain within 10 days of finding out about the decision, as required under the policy.

Whois records compiled by DomainTools show that the domain was instead deleted at in early April, and subsequently re-registered with a different registrar, where it’s currently under dubious-looking privacy.

According to the ICANN compliance notice, Gal Comm says that it deleted the domain because it received a Whois inaccuracy complaint about it.

Assuming that’s correct (and the Whois back in March was blatantly false) we have an interesting tension between policies that seems to have caused a slip-up at the registrar.

But registrars are supposed to lock domains they manage after they become aware of UDRP actions, so allowing the domain to delete seems to be a breach of the policy.

ICANN has given Gal Comm until September 10 to produce its records relating to the domain — and pay past-due accreditation fees — or face possible de-accreditation.

It’s very rare for ICANN to send compliance notices to registrars related to UDRP implementation.

The UK is going nuts about porn and Go Daddy and Nominet are helping

In recent months the unhinged right of the British press has been steadily cajoling the UK government into “doing something about internet porn”, and the government has been responding.

I’ve been itching to write about the sheer level of badly informed claptrap being aired in the media and halls of power, but until recently the story wasn’t really in my beat.

Then, this week, the domain name industry got targeted. To its shame, it responded too.

Go Daddy has started banning certain domains from its registration path and Nominet is launching a policy consultation to determine whether it should ban some strings outright from its .uk registry.

It’s my beat now. I can rant.

For avoidance of doubt, you’re reading an op-ed, written with a whisky glass in one hand and the other being used to periodically wipe flecks of foam from the corner of my mouth.

It also uses terminology DI’s more sensitive readers may not wish to read. Best click away now if that’s you.

The current political flap surrounding internet regulation seems emerged from the confluence of a few high-profile sexually motivated murders and a sudden awareness by the mainstream media — now beyond the point of dipping their toes in the murky social media waters of Twitter — of trolls.

(“Troll” is the term, rightly or wrongly, the mainstream media has co-opted for its headlines. Basically, they’re referring to the kind of obnoxious assholes who relentlessly bully others, sometimes vulnerable individuals and sometimes to the point of suicide, online.)

In May, a guy called Mark Bridger was convicted of abducting and murdering a five-year-old girl called April Jones. It was broadly believed — including by the judge — that the abduction was sexually motivated.

It was widely reported that Bridger had spent the hours leading up to the murder looking at child abuse imagery online.

It was also reported — though far less frequently — that during the same period he had watched a loop of a rape scene from the 2009 cinematic-release horror movie Last House On The Left

He’d recorded the scene on a VHS tape when it was shown on free-to-air British TV last year.

Of the two technologies he used to get his rocks off before committing his appalling crime, which do you think the media zeroed in on: the amusingly obsolete VHS or the golly-it’s-all-so-new-and-confusing internet?

Around about the same time, another consumer of child abuse material named Stuart Hazell was convicted of the murder of 12-year-old Tia Sharp. Again it was believed that the motive was sexual.

While the government had been talking about a porn crackdown since 2011, it wasn’t until last month that the prime minister, David Cameron, sensed the time was right to announce a two-pronged attack.

First, Cameron said he wants to make it harder for people to access child abuse imagery online. A noble objective.

His speech is worth reading in full, as it contains some pretty decent ideas about helping law enforcement catch abusers and producers of abuse material that weren’t well-reported.

But it also contained a call for search engines such as Bing and Google to maintain a black-list of CAM-related search terms. People search for these terms will never get results, but they might get a police warning.

This has been roundly criticized as unworkable and amounting to censorship. If the government’s other initiatives are any guide, it’s likely to produce false positives more often than not.

Second, Cameron said he wants to make internet porn opt-in in the UK. When you sign up for a broadband account, you’ll have to check a box confirming that you want to have access to legal pornography.

This is about “protecting the children” in the other sense — helping to make sure young minds are not corrupted by exposure to complex sexual ideas they’re almost certainly not ready for.

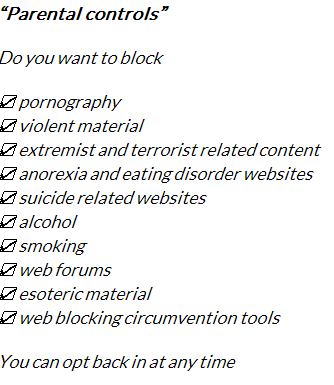

The Open Rights Group has established that the opt-in process will look a little like this:

Notice how there are 10 categories and only one of them is related to pornography? As someone who writes about ICANN on a daily basis, I’m pretty worried about “esoteric materials” being blocked.

As a related part of this move, the government has already arranged with the six largest Wi-Fi hot-spot operators in the country to have porn filters turned on by default.

I haven’t personally tested these networks, but they’re apparently using the kind of lazy keyword filters that are already blocking access to newspaper reports about Cameron’s speech.

Censorship, in the name of “protecting the children” is already happening here in the UK.

Which brings me to Nominet and Go Daddy

Last Sunday, a guy called John Carr wrote a blog post about internet porn in the UK.

I can’t pretend I’ve ever heard of Carr, and he seems to have done a remarkably good job of staying out of Google, but apparently he’s a former board member of the commendable CAM-takedown charity the Internet Watch Foundation and a government adviser on online child safety.

He’d been given a preview of some headline-grabbing research conducted by MetaCert — a web content categorization company best known before now for working with .xxx operator ICM Registry — breaking down internet porn by the countries it is hosted in.

Because the British rank was surprisingly high, the data was widely reported in the British press on Monday. The Daily Mail — a right-wing “quality” tabloid whose bread and butter is bikini shots of D-list teenage celebrities — on Monday quoted Carr as saying:

Nominet should have a policy that websites registered under the national domain name do not contain depraved or disgusting words. People should not be able to register websites that bring disgrace to this country under the national domain name.

Now, assuming you’re a regular DI reader and have more than a passing interest in the domain name industry, you already know how ludicrous a thing to say this is.

Network Solutions, when it had a monopoly on .com domains, had a “seven dirty words” ban for a long time, until growers of shitake mushrooms and Scunthorpe Council pointed out that it was stupid.

You don’t even need to be a domain name aficionado to have been forwarded the hilarious “penisland.net” and “therapistfinder.com” memes — they’re as old as the hills, in internet terms.

Assuming he was not misquoted, a purported long-time expert in internet filtering such as Carr should be profoundly, deeply embarrassed to have made such a pronouncement to a national newspaper.

If he really is a government adviser on matters related to the internet, he’s self-evidently the wrong man for the job.

Nevertheless, other newspapers picked up the quotes and the story and ran with it, and now Ed Vaizey, the UK’s minister for culture, communications and creative industries, is “taking it seriously”.

Vaizey is the minister most directly responsible for pretending to understand the domain name system. As a result, he has quite a bit of pull with Nominet, the .uk registry.

Because Vaizey for some reason believes Carr is to be taken seriously, Nominet, which already has an uncomfortably cozy relationship with the government, has decided to “review our approach to registrations”.

It’s going to launch “an independently-chaired policy review” next month, which will invite contributions from “stakeholders”.

The move is explicitly in response to “concerns” about its open-doors registration policy “raised by an internet safety commentator and subsequently reported in the media.”

Carr’s blog post, in other words.

Nominet — whose staff are not stupid — already knows that what Carr is asking for is pointless and unworkable. It said:

It is important to take into account that the majority of concerns related to illegality online are related to a website’s content – something that is not known at the point of registration of a domain name.

But the company is playing along anyway, allowing a badly informed blogger and a credulous politician to waste its and its community’s time with a policy review that will end in either nothing or censorship.

What makes the claims of Carr and the Sunday Times all the more extraordinary is that the example domain names put forward to prove their points are utterly stupid.

Carr published on his blog a screenshot of Go Daddy’s storefront informing him that the domain rapeher.co.uk is available for registration, and wrote:

www.rapeher.co.uk is a theoretical possibility, as are the other ones shown. However, I checked. Nominet did not dispute that I could have completed the sale and used that domain.

…

Why has it not occurred to Nominet to disallow names of that sort? Nominet needs to institute an urgent review of its naming policies

To be clear, rapeher.co.uk did not exist at the time Carr wrote his blog. He’s complaining about an unregistered domain name.

A look-up reveals that kill-all-jews.co.uk isn’t registered either. Does that mean Nominet has an anti-Semitic registration policy?

As a vegetarian, I’m shocked and appalled to discovered that vegetarians-smell-of-cabbage.co.uk is unregistered too. Something must be done!

Since Carr’s post was published and the Sunday Times and Daily Mail in turn reported its availability, five days ago, nobody has registered rapeher.co.uk, despite the potential traffic the publicity could garner.

Nobody is interested in rapeher.co.uk except John Carr, the Sunday Times and the Daily Mail. Not even a domainer with a skewed moral compass.

And yet Go Daddy has took it upon itself, apparently in response to a call from the Sunday Times, to preemptively ban rapeher.co.uk, telling the newspaper:

We are withdrawing the name while we carry out a review. We have not done this before.

This is what you see if you try to buy rapeher.co.uk today:

Is that all it takes to get a domain name censored from the market-leading registrar? A call from a journalist?

If so, then I demand the immediate “withdrawal” of rapehim.co.uk, which is this morning available for registration.

Does Go Daddy not take male rape seriously? Is Go Daddy institutionally sexist? Is Go Daddy actively encouraging male rape?

These would apparently be legitimate questions, if I was a clueless government adviser or right-leaning tabloid hack under orders to stir the shit in Middle England.

Of the other two domains cited by the Sunday Times — it’s not clear if they were suggested by Carr or MetaCert or neither — one of them isn’t even a .co.uk domain name, it’s the fourth-level subdomain incestrape.neuken.co.uk.

There’s absolutely nothing Nominet, Go Daddy, or anyone else could do, at the point of sale, to stop that domain name being created. They don’t sell fourth-level registrations.

The page itself is a link farm, probably auto-generated, written in Dutch, containing a single 200×150-pixel pornographic image — one picture! — that does not overtly imply either incest or rape.

The links themselves all lead to .com or .nl web sites that, while certainly pornographic, do not appear on cursory review to contain any obviously illegal content.

The other domain cited by the Daily Mail is asian-rape.co.uk. Judging by searches on several Whois services, Google and Archive.org, it’s never been registered. Not ever. Not even after the Mail’s article was published.

It seems that the parasitic Daily Mail really, really doesn’t understand domain names and thought it wouldn’t make a difference if it added a hyphen to the domain that the Sunday Times originally reported, which was asianrape.co.uk.

I can report that asianrape.co.uk is in fact registered, but it’s been parked at Sedo for a long time and contains no pornographic content whatsoever, legal or otherwise.

It’s possible that these are just idiotic examples picked by a clueless reporter, and Carr did allude in his post to the existence of .uk “rape” domains that are registered, so I decided to go looking for them.

First, I undertook a series of “rape”-related Google searches that will probably be enough to get me arrested in a few years’ time, if the people apparently guiding policy right now get their way.

I couldn’t find any porn sites using .uk domain names containing the string “rape” in the first 200 results, no matter how tightly I refined my query.

So I domain-dipped for a while, testing out a couple dozen “rape”-suggestive .co.uk domains conjured up by my own diseased mind. All I found were unregistered names and parked pages.

I Googled up some rape-themed porn sites that use .com addresses — these appear to exist in abundance, though few appear to contain the offending string in the domain itself — and couldn’t find any that have bothered to even defensively register their matching .co.uk.

So I turned to Alexa’s list of the top one million most-popular domains. Parsing that (.csv), I counted 277 containing the string “rape”, only 32 of which (11%) could be loosely said to be using it in the sense of a sexual assault.

Whether those 32 sites contain legal or illegal pornographic content, I couldn’t say. I didn’t check. None of them were .uk addresses anyway.

Most of the non-rapey ones were about grapes.

I’m not going to pretend that my research was scientific, neither am I saying that there are no rape-themed .co.uk porn sites out there, I’m just saying that I tried for a few hours to find one and I couldn’t.

What I did find were dozens of legitimate uses of the string.

So if Nominet bans the word “rape” from domain name registrations under .uk — which is what Carr seems to want to happen — what happens to rapecrisis.org.uk?

Does the Post Office have to give up grapevine.co.uk, which it uses to help prevent crime? Does the eBay tools provider Terapeak have to drop its UK presence? Are “skyscrapers” too phallic now? Is the Donald Draper Fan Club doomed?

And what about the fine fellows at yorkshirerapeseedoil.co.uk or chilterncoldpressedrapeseedoil.co.uk?

If these examples don’t convince you that a policy of preemptive censorship would be damaging and futile, allow me to put the question in terms the Daily Mail might understand: why does Ed Vaizey hate farmers?

Two banks go down after forgetting to renew domains

Two UK banks suffered downtime over the weekend after apparently failing to renew their domain name registrations.

Clydesdale Bank and Yorkshire Bank, which offer online banking services at cbonline.co.uk and ybonline.co.uk respectively, both blamed a “systems update” for the downtime.

But some customers reported seeing a registrar’s renewal page when they attempted to access the sites, and others are reportedly still seeing difficulties consistent with DNS propagation delays.

Both domain names have expiry dates of July 26, according to Whois records.

Thankfully, the banks, both of which are owned by National Australia Bank, managed to retain control of their domains. If they’d fallen into third party hands things could have been a lot worse.

Combined, the banks have revenue of a couple of billion pounds.

In the wake of .amazon, IP interests turn on the GAC

Intellectual property interests got a wake-up call at ICANN 47 in Durban this week, when it became clear that they can no longer rely upon the Governmental Advisory Committee as a natural ally.

The GAC’s decision to file a formal consensus objection against Amazon’s application for the .amazon gTLD prompted a line of IP lawyers to queue up at the Public Forum mic to rage against the GAC machine.

As we reported earlier in the week, the GAC found consensus to its objection to .amazon after the sole hold-out government, the United States, decided to keep quiet and allow other governments to agree.

This means that the ICANN board of directors will now be presented with a “strong presumption” that .amazon should be rejected.

With both previous consensus objections, against .africa and .gcc, the board has rejected the applications.

The objection was pushed for mainly by Brazil, with strong support from Peru, Venezuela and other Latin American countries that share the Amazon region, known locally as Amazonas.

During a GAC meeting on Tuesday, statements of support were also made by countries as diverse as Russia, Uganda and Trinidad and Tobago.

Brazil said Amazon is a “very important cultural, traditional, regional and geographical name”. Over 50 million Brazilians live in the region, he said.

The Brazilian Congress discussed the issue at length, he said.

The Brazilian Internet Steering Committee was also strongly against .amazon, he said, and there was a “huge reaction from civil society” including a petition signed by “thousands of people”.

All the countries in the region also signed the Montevideo Declaration (pdf), which resolves to oppose any attempts to register .amazon and .patagonia in any language, in April.

It doesn’t appear to be an arbitrary decision by one government, in other words. People were consulted.

The objection did not receive a GAC consensus three months ago in Beijing only because the US refused to agree, arguing that governments do not have sovereign rights over geographic names.

But prior to Durban, without changing its opinion, the US said that it would not stand in the way of consensus.

It seems that there may have been bigger-picture political concerns at play. The NTIA, which represents the US on the GAC, is said to have had its hands tied by its superiors in Washington DC.

Did the GAC move the goal posts?

With the decision to object to .amazon already on the public record before the GAC’s Durban communique was formally issued yesterday, Intellectual Property Constituency interests had plenty of time to get mad.

At the Public Forum yesterday, several took to the open mic to slam the GAC’s decision.

Common themes emerged, one of which was the claim that the GAC is retroactively changing the rules about what is and is not a “geographic” string for the purposes of the Applicant Guidebook.

Stacey King, senior corporate counsel with Amazon, said:

Prior to filing our applications Amazon carefully reviewed the Applicant Guidebook; we followed the rules. You are now being asked to significantly and retroactively modify these rules. That would undermine the hard-won international consensus to the detriment to all stakeholders. I repeat, we followed these rules.

It’s true that the string “amazon” is not on any of the International Standards Organization lists that ICANN’s Geographic Names Panel used to determine what’s “geographic”.

The local-language string “Amazonas” appears four times, representing a Brazilian state, a Colombian department, a Peruvian region and a Venezuelan state; Amazon isn’t there.

But Amazon is wrong about one thing.

By filing its objection, the GAC is not changing the rules about geographic names, it’s exercising its entirely separate but equally Guidebook-codified right to object to any application for any reason.

That’s part of the Applicant Guidebook too, and it’s a part that the IPC has never previously objected to.

Amazon was not alone making its claim about retroactive changes. IPC president Kristina Rosette, wearing her hat as counsel for former .patagonia applicant Patagonia Inc, said:

Patagonia is deeply disappointed by and concerned about the breakdown of the new gTLD process. Consistent with the recommendations and principles established in connection with that process, Patagonia fully expected its .patagonia application to be evaluated against transparent and predictable criteria, fully available to applicants prior to the initiation of the process.

Yet, its experience demonstrates the ease with which one stakeholder can jettison rules previously agreed upon after an extensive and thorough consultation.

That’s not consistent with the IPC’s position.

The IPC just last month warmly welcomed (pdf) the GAC’s Beijing advice, stating that the after-the-fact “safeguards” it demanded for all new gTLDs should be accepted.

Apparently, it’s okay for the GAC to move the goal posts for gTLD applicants when its advice is about Whois accuracy, but when it files an objection — perfectly compliant with the GAC Advice section of the Guidebook — that interferes with the business objectives of a big trademark owner, that’s suddenly not cool.

The IPC also did not challenge the GAC Advice process when it was first added to the Applicant Guidebook in the April 2011 draft.

At that time, the GAC had responded to intense lobbying by IP interests and was fighting their corner with the ICANN board, demanding stronger trademark protections in the new gTLD program.

If the IPC now finds itself arguing against the application of the GAC Advice rule, perhaps it should consider whether speaking up earlier might have been a good idea.

Rosette tried to substantiate her remarks by referring back to previous GAC advice, specifically a May 26, 2011 letter in which she said the GAC “formally accepted” the Guidebook’s definition of geographic strings.

However, that letter (pdf) has a massive caveat. It says:

Given ICANN’s clarifications on “Early Warning” and “GAC Advice” that allow the GAC to require governmental support/non-objection for strings it considers to be geographical names, the GAC accepts ICANN’s interpretation with regard to the definition of geographic names.

In other words, “The GAC is happy with your list, as long as we can add our own strings to it at will later”.

Rosette’s argument that the GAC has changed its mind, in other words, does not hold.

It wasn’t just IP interests that stood up against the .amazon decision, however. The IPC found an unlikely ally in the Registries Stakeholder Group, represented at the Public Forum by Verisign’s Keith Drazek.

Drazek sought to link the “retroactive changes” on geographic strings to the “retroactive changes” the GAC has proposed in relation to the so-called Category 1 strings — which would have the effect of demanding that hundreds of regular gTLD bids convert into de facto “Community” applications. He said:

While different stakeholders have different views about particular aspects of the GAC advice, we have a shared concern about the portions of that advice that constitute retroactive changes to the Applicant Guidebook around the issues of sovereign rights, undefined and unexplained geographic sensitivities, sensitive industry strings, regulated strings, etc.

This appears to be one of those rare instances where the interests of registries and the interests of IP owners are aligned. The registries, however, have at least been consistent, complaining about the GAC Advice process as soon as it was published in April 2011.

There’s also a big difference between the substance of the advice that they’re currently complaining about: the objection against .amazon followed the Guidebook rules on GAC Advice almost to the letter, whereas the Category 1 advice came completely out of the left field, with no Guidebook basis to cling to.

The GAC in the case of .amazon followed the rules. The rules are stupid, but the time to complain about that was before paying your $185,000 to apply.

If anyone is trying to change the rules after the fact, it’s Amazon and its supporters.

Is the GAC breaking the law?

Another recurring theme throughout yesterday’s Public Forum commentary was the idea that international trademark law does not support the GAC’s right to object to .amazon.

I’m going to preface my editorializing here with the usual I Am Not A Lawyer disclaimer, but it seems to be a pretty thin argument.

Claudio DiGangi, secretary of the IPC and external relations manager at the International Trademark Association, was first to comment on the .amazon objection. He said:

INTA strongly supports the recent views expressed by the United States. In particular, that it does not view sovereignty as a valid basis for objecting to the use of terms, and we have concerns about the effect of such claims on the integrity of the process.

J Scott Evans, head of domains at Yahoo, who left the IPC for the Business Constituency recently (apparently after some kind of disagreement) was next. He said:

There is no international recognition of country names as protection and they cannot trump trademark rights. So giving countries a block on a name violates international law. So you can’t do it.

There were similar comments along the same lines.

Heather Forrest, a senior lecturer at an Australian university and former AusRegistry employee, said she had conducted a doctoral thesis (available at Amazon!) on the rights of governments over geographic names, with particular reference to the Applicant Guidebook.

She told the Public Forum:

My study was comprehensive. I looked at international trade law, unfair competition law, intellectual property law, geographic indications, sovereign rights and human rights. As the board approved the Applicant Guidebook, I completed my study and found that there is not support in international law for priority or exclusive right of states in geographic names and found that there is support in international law for the right of non-state others in geographic names.

Kiran Malancharuvil, whose job until recently was to lobby the GAC for special protections for her client, the International Olympic Committee, now works for MarkMonitor. Calling for the ICANN board to reject the GAC’s advice on .amazon, she said at the Public Forum:

To date, governments in Latin America including the Amazonas community countries have granted Amazon over 130 trademark registrations that have been in continuous use by Amazon since 1994 without challenge. Additionally, Amazon has used their brand within domain names including some registered by MarkMonitor and including registrations in Amazonas community ccTLDs without objection.

Amazonas community countries and all other nations who have signed the TRIPS agreement have obligated themselves to maintain and protect these trademark registrations. Despite these granted rights, members of the community signed the Montevideo declaration and resolved to reject Amazon and Patagonia in any language as well as any other top-level domains referring to them. This declaration appears inconsistent with national and international law.

Having read TRIPS — the World Trade Organization’s Trade Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights treaty — this morning, I’m still none the wiser how it relates to .amazon.

It’s a treaty that sought to create some uniformity in how trademarks and other types of intellectual property are handled globally, and domain names are not mentioned once.

As far as I can tell, nobody is asking Amazon to change its name and nobody’s trying to take away its trademarks. Nobody’s even trying to take away its domain names.

If the international law argument is simply that the GAC and/or ICANN cannot prevent a company with a trademark from getting its mark as a TLD, as Yahoo’s Evans suggested, it seems to me that quite a lot of the new gTLD program would have to be rewritten.

We’re already seeing Legal Rights Objections in which an applicant with a trademark is losing against an applicant without a trademark.

Is that illegal too? Was it illegal for ICANN to create an LRO process that has allowed Donuts (no trademark) to beat Express LLC (with trademark) in a fight over .express?

What about other protections in the Guidebook?

ICANN already bans two-character gTLDs, on the basis that they could interfere with future ccTLDs — protecting the geographic rights of countries that do not even exist — which disenfranchises companies with two-letter trademarks, such as BT and HP.

What about 888, the poker company, and 3, the mobile phone operator? They have trademarks. Should ICANN be forced to allow them to have numeric gTLDs, despite the obvious risks?

The Guidebook already bans country names outright, and says thousands of other geographic terms need government support or will be rejected. Is this all illegal?

If the argument is that trademarks trump all, ICANN may as well throw out half the Guidebook.

Now what?

Unlike .patagonia, which dropped out of the new gTLD program last week (we’ll soon discover whether that was wise), the objection to .amazon will now go to ICANN’s board of directors for consideration.

While the Guidebook calls for a “strong presumption” that the board will then reject the application, board member Chris Disspain said yesterday that outsiders should not assume that it will simply rubber-stamp the GAC’s advice.

In both previous cases, the outcome has been a rejection of the application, however, so it’s not looking great for Amazon.

First three new gTLD objections thrown out

Three objections against new gTLD applications have been thrown out by the World Intellectual Property Organization, two of them on the basis that they were blatant attempts to game the system.

The objections were all Legal Rights Objections. Essentially, they’re attempts by the objectors to show that for ICANN to approve the gTLD would infringe their existing trademark rights.

The applications being objected to were Google’s .home, SC Johnson’s .rightathome and Vipspace Enterprises .vip.

The decisions are of course completely unprecedented. No LROs have ever been decided before.

Let’s look at each in turn.

Google’s .home

The objector here was Defender Security Company, a home security company, which has also applied for .home and has objected to nine of its competitors for the string.

Basically, the objection was thrown out (pdf) because it was a transparent attempt to game the trademark system in order to secure a potentially lucrative gTLD.

Defender appears to have bought the application, along with associated companies, domains, social media accounts and trademarks, from CGR E-Commerce, a company owned by .music applicant Constantine Roussos.

The panelist in the case apparently doesn’t have a DomainTools subscription and couldn’t make the Roussos link from historical Whois records, but it’s plain to see for those who do.

The case was brought on the basis of a European Community trademark on the term “.home”, applied for in December 2011, just a few weeks before ICANN opened the new gTLD application window, and a US trademark on “true.home” applied for a few months later.

The objector also owned dothome.net, one of many throwaway Go Daddy domain name resellers Roussos set up in late 2011 in order to assert prior rights to TLDs he planned to apply for.

The panelist saw through all the nonsense and rejected the objection due to lack of standing.

Here’s the money quote:

The attempted acquisition of trademark rights appears to have been undertaken to create a basis for filing the Objection, or defending an application. There appears to have been no attempt to acquire rights in or use any marks until after the New gTLD Program had been announced, specifically two weeks before the period to file applications for new gTLDs was to open.

For the EC trademark, lack of standing was found because Defender didn’t present any evidence that it actually owned the company, DotHome Ltd, that owned the trademark.

For the US trademark, which is still not registered, the panelist seems to have relied upon UDRP precedent covering rights in unregistered trademarks in his decision to find lack of standing.

The panelist also briefly addresses the Applicant Guidebook criteria for LROs, although it appears he was not obliged to, and found Defender’s arguments lacking.

In summary, it’s a sane decision that appears to show that you can’t secure a gTLD with subterfuge and bogosity.

It’s not looking good for the other eight objections Defender has filed.

Vipspace Enterprises’ .vip

This is another competitive objection, filed by one .vip applicant against another.

The objector in this case is German outfit I-Registry, which has applied for four gTLDs. The respondent is Vipspace, which has only applied for .vip.

In this case, both companies have applied for trademarks, one filed one month before the other.

The panelist’s decision focuses, sanely again, on the generic nature of the string in question.

Because both trademarks were filed for the word “VIP” meaning “Very Important Person”, which is the intended meaning of both applications, it’s hard to see how either is a proper brand.

The panelist wrote (pdf):

while SOAP, for example, may be a perfectly satisfactory trade mark for cars, it cannot serve as a trade mark for the cleaning product “soap”.

…

While the parties have used the term, “VIP”, in various forms on their website to indicate the manner in which the term will be used if they are successful in being awarded the domain, there is nothing before the Panel (beyond mere assertion) to show that either of them has yet traded under their marks sufficiently to displace the primary descriptive meaning of the term and establish a brand or at all.

In other words, it’s a second case of a WIPO panelist deciding that getting, or applying for, a trademark is not enough to grant a company exclusive rights to a new gTLD string.

Sanity, again, prevails.

SC Johnson’s .rightathome

While it contains the word “home”, this is a completely unrelated case with a different objector and a different panelist.

The objector here was Right At Home, a Nebraska-based international provider of in-home elderly care services. The applicant is a subsidiary of the well-known cosmetics company SC Johnson, which uses “Right@Home” as a brand.

It appears that both objector and applicant have really good rights to the string in question, which makes the panelist’s decision all the more interesting.

The way the LRO is described in ICANN’s new gTLD Applicant Guidebook, there are eight criteria that must be weighed by the panelist.

In this case, the panelist does not provide a conclusion showing how the weighting was done, but rather discusses each point in turn and decides whether the evidence favors the objector or the applicant.

The applicant here won on five out of the eight criteria.

The fact that the two companies offer different products and/or services, accompanied by the fact that the phrase “Right At Home” is in use by other companies in addition to the complainant and respondent appears to have been critical in tipping the balance.

In short, the panelist appears to have decided (pdf) that because SC Johnson did not apply for .rightathome in bad faith, and because it’s unlikely internet users will think the gTLD belongs to Right At Home, the objection should be rejected.

I am not a lawyer, but it appears that the key takeaway from this case is that owning a legitimately obtained brand is not enough to win an LRO if you’re an objector and the new gTLD applicant operates in a different vertical.

This will worry many people.

2013 RAA is illegal, says EU privacy watchdog

European privacy regulators have slammed the new 2013 Registrar Accreditation Agreement, saying it would be illegal for registrars based in the EU to comply with it.

The Article 29 Working Party, which comprises privacy regulators from the 27 European Union nations, had harsh words for the part of the contract that requires registrars to store data about registrants for two years after their domains expire.

In a letter (pdf) to ICANN last month, Article 29 states plainly that such provisions would be illegal in the EU:

The fact that these personal data can be useful for law enforcement does not legitimise the retention of these personal data after termination of the contract. Because there is no legal ground for the data processing, the proposed data retention requirement violates data protection law in Europe.

The 2013 RAA allows any registrar to opt out of the data retention provisions if it can prove that to comply would be illegal its own jurisdiction.

The Article 29 letter has been sent to act as blanket proof of this for all EU-based registrars, but it’s not yet clear if ICANN will treat it as such.

The letter goes on to sharply criticize ICANN for allowing itself to be used by governments (and big copyright interests) to circumvent their own legislative processes. It says:

The fact that these data may be useful for law enforcement (including copyright enforcement by private parties) does not equal a necessity to retain these data after termination of the contract.

…

the Working Party reiterates its strong objection to the introduction of data retention by means of a contract issued by a private corporation in order to facilitate (public) law enforcement.

If there is a pressing social need for specific collections of personal data to be available for law enforcement, and the proposed data retention is proportionate to the legitimate aim pursued, it is up to national governments to introduce legislation

So why is ICANN trying to get many of its registrars to break the law?

While it’s tempting to follow the Article 29 WP’s reasoning and blame law enforcement agencies and the Governmental Advisory Committee, which pushed for the new RAA to be created in the first place, the illegal data retention provisions appear to be entirely ICANN’s handiwork.

The original law enforcement demands (pdf) say registrars should “securely collect and store” data about registrants, but there’s no mention of the period for which it should be stored.

And while the GAC has expressly supported the LEA recommendations since 2010, it has always said that ICANN should comply with privacy laws in their implementation.

The GAC does not appear to have added any of its own recommendations relating to data retention.

ICANN can’t claim it was unaware that the new RAA might be illegal for some registrars either. The Article 29 WP told it so last September, causing ICANN to introduce the idea of exemptions.

However, the European Commission’s GAC representative then seemed to dismiss the WP’s concerns during ICANN’s public meeting in Toronto last October.

Perhaps ICANN was justifiably confused by these mixed messages.

According to Michele Neylon, chair of the Registrars Stakeholder Group, it has yet to respond to European registrars’ inquiries about the Article 29 letter, which was sent June 6.

“We hope that ICANN staff will take the letter into consideration, as it is clear that the data protection authorities do not want create extra work either for themselves or for registrars,” Neylon said.

“For European registrars, and non-European registrars with a customer base in the EU, we look forward to ICANN staff providing us with clarity on how we can deal with this matter and respect EU and national law,” he said.

New gTLD registry contract approved, but applicants left hanging by GAC advice

ICANN has approved the standard registry contract for new gTLD registries after many months of controversy.

But its New gTLD Program Committee has also decided to put hundreds more applications on hold, pending talks with the Governmental Advisory Committee about its recent objections.

The new Registry Agreement is the baseline contract for all new gTLD applicants. While some negotiation on detail is possible, ICANN expects most applicants to sign it as is.

Its approval by the NGPC yesterday — just a couple of days later than recently predicted by ICANN officials — means the first contracts with applicants could very well be signed this month.

The big changes include the mandatory “Public Interest Commitments” for abuse scanning and Whois verification that we reported on last month, and the freeze on closed generics.

But a preliminary reading of today’s document suggests that the other changes made since the previous version, published for comment by ICANN in April, are relatively minor.

There have been no big concessions to single-registrant gTLD applicants, such as dot-brands, and ICANN admitted that it may have to revise the RA in future depending on how those discussions pan out.

In its resolution, the NGPC said:

ICANN is currently considering alternative provisions for inclusion in the Registry Agreement for .brand and closed registries, and is working with members of the community to identify appropriate alternative provisions. Following this effort, alternative provisions may be included in the Registry Agreement.

But many companies that have already passed through Initial Evaluation now have little to worry about in their path to signing a contract with ICANN and proceeding to delegation.

“New gTLDs are now on the home stretch,” NGPC member Chris Disspain said in a press release “This new Registry Agreement means we’ve cleared one of the last hurdles for those gTLD applicants who are approved and eagerly nearing that point where their names will go online.”

Hundreds more, however, are still in limbo.

The NGPC also decided yesterday to put a hold on all “Category 1” applications singled out for advice in the Governmental Advisory Committee’s Beijing communique.

That’s a big list, comprising hundreds of applications that GAC members had concerns about.

The NGPC resolved: “the NGPC directs staff to defer moving forward with the contracting process for applicants who have applied for TLD strings listed in the GAC’s Category 1 Safeguard Advice, pending a dialogue with the GAC.”

That dialogue is expected to kick off in Durban a little over a week from now, so the affected applicants may not find themselves on hold for too long.

Negotiations, however, are likely to be tricky. As the NGPC’s resolution notes, most people believe the Beijing communique was “untimely, ill-conceived, overbroad, and too vague to implement”.

Or, as I put it, stupid.

By the GAC’s own admission, its list of strings is “non-exhaustive”, so if the delay turns out to have a meaningful impact on affected applicants, expect all hell to break loose.

Recent Comments